IMAGE, OBSCURITY & INTERPRETATION

henry holmes smith

Human beings are able to invent a vocabulary for any difficult subject that sufficiently arouses their interest. They do this for their gods, their sciences, their taboos and their arts. Among civilized persons an art without a literature is a naked art and raw. In this state we find photography, young, inferior, the victim of supreme indifference and misunderstanding. At this time it is unfashionable to discourse on the art and meaning of photography ; some persons assert it is neither possible nor desirable to do so. I see this lack, instead, merely as an index of a meager supply of collectors, dealers, curators and others who really have their minds on photography. Briefly, photographs lack the prestige and dignity accorded even postage stamps as items to collect. (Not long ago in a leading New York art dealer’s shop, two Paul Strand photographs, one a platinum print made in 1917, the other a platinotype, I believe, made in the late 1920’s, sold for $25.00 apiece.)

Compared with the abundant repetitious nonsense written about techniques and equipment and the accompanying induced hysteria over these subjects, intelligent critical literature on photographs is barely discernible. No other art of comparable importance in our time possesses a body of literature more unbalanced or generally humdrum. Equally depressing is the massive indifference with which many first-rate photographers view this lack.

This condition has not been corrected by the false authority now assumed by advertisers and editors who are without question the most active and influential contemporary patrons of this art. Unfortunately they need only a fraction of all photography, images deliberately and arbitrarily limited in depth and intensity for well-known reasons to fit familiar requirements. Consequently, if these patrons pronounce a judgment on work for which they have no use, it is frequently meaningless and often impertinent.

From editors and advertisers has also come a questionable convention of viewing a photograph: an insistence on such responses as immediate awareness of what the photograph "says.” Unfortunately this practice implies there is no penalty for haste, impatience, narrowness or plain thick-headedness. Certainly a "reader-on-the-run” may judge almost every photograph used in buying and selling and all those printed as popular "information,” by these popular standards. (Such photographs have about the same relationship to photographs of reality as an artificial lure has to natural fish food.) Yet when these same standard responses are used to justify attacks upon important personal images beyond the needs of present-day periodicals, the absolute irrelevance of such criticism must be emphasized. (The pertinent fact is that the images under criticism remain unpublished ; this judgment is exact, unarguable and fitting. The right not to publish is the editor’s or publisher’s, but the privilege of remaining indifferent to such images is not passed on to the public. One editor categorically announced that he could not remember having seen a single "important” photograph which had not been published.)

Seen in this perspective, the dispute between the proponents of photographic journalism (which embraces a wide and important range of naturalistic and conventional photographic images) and those who like to look also at nonjournalistic photography (where one may find some of the most secure, independent and inventive images of our time) becomes a more even contest. (Obviously this is not an invitation to editors to look carefully at photographs they do not need or cannot print; they will print them when they need them. If they put their minds to it, these same editors could also produce a body of genuine and worthwhile criticism. As I see it they lack both the time and inclination to do this.)

• There is no harm in a photographer deciding to take an advertiser or a publisher as his patron, providing the wages and hours are satisfactory. There is no sensible objection to a person deciding to be his own patron, when he can. In our day this may be for some individuals the only way they can provide support for their work. The slight offense this behavior may give the practical-minded may be discounted considerably. One or two important advantages accrue to the photographer who is his own patron: he can think and feel and work in his own tempo and when he does work he can take his time and be himself. There are some persons today who see these as rich rewards. Further, in our time, when a person with something to "say” uses photography carefully, even deliberately, his images may turn out to be difficult, obscure, even "precious” (in the sense that some metals and stones are precious) . Once the editor’s conventional approach to photographs is put aside, we can face these intense images with a greater sense of anticipation. In this anticipation, as has been pointed out elsewhere ("Five Photographs by Aaron Siskind,” aperture, Vol. 5:3) lies the key to photographic form. The image anticipated must link satisfyingly with the image discovered in a photograph.

In any attack on an "obscure” photograph, if the complaint is clearly stated, one can locate some combination of frustration because the photograph does not yield its meaning (or meanings) at once, and exasperation because the photograph "says” something the viewer disapproves of or does not picture what the viewer wishes to see. A picture worth any study for its major meanings must be examined for what the photographer is showing and not for what a viewer may wish had been his subject. We may even find that what we first saw as "obscure,” or "precious,” or "inconsequential,” is something overwhelmingly personal, which we may not wish to see at all. More important we may discover that the immediate recognition of the literal subject matter in a photograph and the eventual comprehension of the photograph’s meaning or image, are distinct and completely different experiences. The rapidity with which information is imparted by a photograph is an inadequate index of the importance of either the photograph or the information. Some snapshots, some mediocre imitative work, and some photographs generally thought of as distinguished and important today, all make direct, clear statements each on its own level. Probably an equally large body of work in each of these classes could be found in which the "statements” would be much more difficult to interpret. The reasons works of art are difficult have been examined in detail by I. A. Richards in his useful book, PRACTICAL CRITICISM (Harvest Book 16, Harcourt, Brace, New Tbrk, pp. 1215). Even though he is discussing the difficulties encountered in reading English poetry, they are similar to the problems facing a person trying to comprehend photographs. Richards’ list follows (I have paraphrased and changed some terms to make them fit the parallel problem in photography) :

1. Difficulty in making out the plain sense of the picture, to "see” what the picture is portraying.

2. Difficulty in sensuous apprehension of the rhythms, tones, textures, shapes, all the formal elements of the picture. This is particularly true of photographs which have not been made from "orthodox” subject matter.

3. Difficulty in establishing the pertinent imagery. This failure is often the result of anticipating the wrong image.

4. Misleading effects, the result of an observer’s being reminded of some personal scene or adventure.

5. Stock responses, where the picture involves views and emotions already fully prepared in the viewer’s mind.

6. Sentimentality, overfacility in certain emotional directions.

7. Inhibition, incapacity to move in certain emotional directions.

8. Doctrinal adhesions, where the subject matter of the picture involves the viewer with ideas or beliefs, true or false, about the world.

9. Technical presuppositions, for example assuming that a technique which has shown its ineptitude for one purpose is discredited for all. (This is a constantly recurring response in photography.)

10. General critical preconceptions, prior demand made on photography as a result of theories, conscious or unconscious about its nature and value, intervene endlessly between the viewer and photograph.

As soon as we agree that some photographs may function incompletely on first sight, we obtain a wider selection of photographs for "reading,” not all of which are bad. t this is not a blanket defense of obscurity. Upon confronting a difficult or puzzling photograph, an individual must decide whether the artist is being unnecessarily obscure or the viewer, himself, is being unduly obtuse. We should be cautious about resolving all such questions in our favor; it is unlikely that anyone will extend his indulgence in this respect beyond his limit of endurance. Richards’ list of our human limitations, however, may induce a greater generosity on our part than we have hitherto accorded photographs. Probably everyone will find intolerable some important work even in the art he loves best and knows most about.

• The First Indiana University Photography Workshop (reported aperture, 5:1), held in June 1956, adapted the techniques of I. A. Richards, which he had used for a number of years in obtaining comments on poems, (PRACTICAL CRITICISM gives a number of excellent examples of the results of this method with poetry.) Some elementary assumptions were made in setting up the workshop program: (1) mature photographers are capable of providing complete images, which may be examined and "understood” without correction or elision; (2) sometimes these photographers may be articulate about what they have done ; (3) intelligent attention to and discussion of a photograph may help some individuals appreciate more clearly some difficult pictures.

• Among the many pitfalls, hazards and difficulties which were encountered during the workshop may be listed those Richards mentions in the work cited (pp. 292-315) "gaps in readers’ equipment, lack of general experience of life and lack of experience with the art under study, the inability to construe meaning, construing being a more difficult performance than generally supposed, the facility with which usual meanings appear when not wanted, presuppositions as to what is to be admired and despised,” "too sheer a challenge to the readers’ unsupported self,” "bewilderment resulting from any attempt to read without the guidance of authority.” He also mentions the feeling of excessive strain placed upon anyone who attempts to study a work of art without some assurance that the work is worthwhile.

The main method of group picture study made use of projected lantern slides. This provided nearly identical viewing conditions for everyone and minimized information about the maker. Everyone was asked to write down his important responses to each photograph, in the order in which they came to him. Later in the session these were read aloud and discussed. Comparison of responses usually resulted in a number of the viewers taking a position closer to one another about the photograph, by agreeing to the greater accuracy, reasonableness or probability of one interpretation over some of the others. Finally the photographer’s statement, if he had provided one, was compared with the group reactions.

As Jerome Liebling wrote in the preface to the statement that accompanied his photograph used during the workshop, "It is because the various arts have such intrinsic and compelling modes that the artist strives for attainment within specific form. I think this might possibly hinder an easy 'verbalization’ of a visual art. Nevertheless I feel strongly that the attempt should be made.”

By now it is clear that some of us do and some of us don’t. Reasons given by those who don’t believe in verbalization range from the usual warnings of "great danger,” (temptation of the artist to redeem his mediocre work with verbal justifications, excessive posturing by the artist in a medium other than his own) to the flat expression of distaste for systematic examination of the art (some say it spoils the work for them). Richards has an answer "The fear that to look too closely (at a work of art) may be damaging to what we care about is a sign of a weak or ill-balanced interest . . . Those who 'care too much for poetry’ to examine it closely are probably flattering themselves.”

Other methods of picture viewing include examination of the actual print by passing it around the study table. Conjectures were made orally, and other persons present modified these in the light of what they "saw.” Another method was to pass the print completely around the group, permitting each person to study it as long as he felt necessary. During this time no remarks about the image were made. Then conclusions were reported in writing. Whether the responses were made orally or in writing, whether they were made in turn, during the viewing of the photograph or after all had seen the picture, they varied as much as Richards’ report on similar responses to poetry would have led one to expect.

• There were, in all, four distinct problems: (1) the problem of believing that the photograph was "important” enough to spend any time on; (2) the discovery of applicable methods, devices or concepts for working with the picture ; (3) development of some scheme of evaluation for appraising the varied responses to the pictures; (4) development of a value scale for appraising the photograph’s merit. Many individuals were immediately ready to make assertions about the fourth problem, usually in strictly personal terms, before anything had been done with the second and third (the first is always an "act of faith”) . This leads me to the conclusion that only photographs deeply felt to be "worthwhile” by the person looking at them should be used in any future study. This should be done, even though it may mean that the entire group will consent to work together on only a few photographs. Consent and interest is paramount to sustained attention.

Some persons upon discovering that they had only limited equipment for dealing with and discussing the photographs, fell into silence. Others, with no more to offer, became almost aggressively sure of themselves. Still others protected themselves with a flippant attitude towards the photographs. All this prevented a sustained attack upon the third problem. The photographer’s suggested interpretation was used as the standard of reference for accuracy.

Group discourse without careful procedure, including verification of inferences by checking against the basic visual facts within the photograph, leads almost as often away from the central point as toward it. All the patience in the world, all the intellectual prodding and plodding, usually produces only wretched, tortured image fragments, a reflection of the viewer’s own state of mind. \ht there are rewards in certain cases when a fleeting moment of insight, from now one member of the viewing group and now another, suddenly brings an approximation of the photographer’s image into mind. It is inspiring to see the effect of this initial insight, how the others cling to it, add to it sensibly and intelligently and often round it out.

It is absolutely necessary to accept the photograph as it is, not try to interpret it and remake it. In one futile session, a Cartier-Bresson image of great power and telling character provoked considerable attack from several viewers. It was called "weak,” and "one of his worst.” ("Alicante, Spain,” 1933, reproduced in the PHOTOGRAPHS OF HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON by Kirstein and Newhall; Museum of Modern Art, 1947, p. 26.)

• Another interesting sally was the attempt of an individual to improve one of Edward Weston’s photographs by trimming one edge. Attitudes such as this constitute a serious obstacle to interpretation. It cannot be denied, however, that these same attitudes may be necessary and appropriate in young photographers with new attitudes toward the image, for whom much of what has been done will be actually distasteful and at the moment without value. As has been suggested on a number of occasions, the act of conscious interpretation may be so repugnant or unnecessary to the photographer who is busy making images, that he should not be asked to participate.

The following remarks from PRACTICAL CRITICISM may provide a needed note of caution at this point:

The wild interpretations of others must not be regarded as the antics of incompetents, but as dangers that we ourselves only narrowly escape, if, indeed, we do . . . The only proper attitude is to look upon a successful interpretation, a correct understanding, as a triumph against odds. We must cease to regard misinterpretation as a mere unlucky accident. We must treat it as the normal and probable event, (p. 315)

. . . the masters of life—the greater poets—sometimes show such an understanding and control of language that we cannot imagine further perfection . . . judged by a much humbler order of perceptions, we can be certain that most 'well-educated’ persons remain, under present-day conditions, far below the level of capacity at which, by social convention, they are supposed to stand. As to the less 'well-educated’ . . . genius apart . . . they inhabit chaos, (pp. 305-306)

These remarks fit the problems of interpreting photography as well as poetry. We are all engaged with a mass of photographs that we barely understand. To paraphrase Richards (p. 291) : The technique of the approach to photography "has not yet received half so much serious study as the technique of polejumping. If it is easy to push up the general level of performance in such 'natural’ activities as running or jumping . . . merely by making a little careful inquiry into the best methods, surely there is reason to expect that investigation into the technique of reading may have even happier results.” In the present state of things, each one must conserve the photography he understands, permitting, when his tolerance is sufficient, the remainder of the art to be conserved and examined elsewhere. Ultimately each of us may find, to our surprise, that our intolerance often rests on ignorance and our misunderstandings, our accusations of obscurity, unintelligibility, or falseness spring from too narrow a view of a medium that offers an intensity of expression and a range of images much greater than is generally seen. I think that paying strict attention to photographs is the most sensible way of finding out about their images. I think that discovering ways of accurately describing what we find will develop the vocabulary we need. With this vocabulary we may develop a body of discourse, much of which will probably be idiotic. Yet, in these conversations and written matter, we may one day find the intelligent literature that must, at last, grace this much neglected art.

FOUR IMAGES READ

The Liebling photograph brought the following response: The arrogant survivor. A vestige of nature. The only living form. The limp shirt, vestige of human hand. Debris, ugliness man’s part. The possible symbolic aspect of the shirt, its whiteness in the dark courtyard, were examined without profit. Not much satisfaction was derived from these conjectures and attention dwindled within a period of about five minutes. This picture was viewed as projected on a screen.

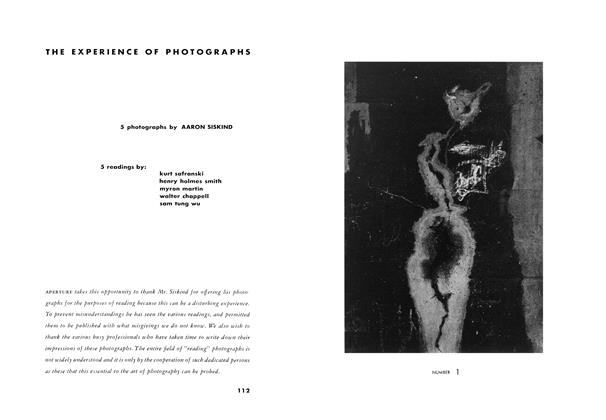

The Siskind photograph was also viewed in the form of a projected lantern slide. For this session, the audience was asked to write down its response in the form of a summarizing statement. These are given here because they are typical of the range of response, and indicate the general level of the audience. (Only a most carefully selected viewing group would produce a closer correspondence of responses.)

A: Abstract generalization: nature is agency; nature’s action. Texture, form, space. Breaking up through texture. Rending into sort of void of unknown—which has stability from black against white. Idea of things

lifting and moving. Compare with Callahan’s gulls and birds. (Harry Callahan’s photographs had been exhibited prior to this study session.)

B : Dark shadows and gray lines.

C: Cracked painted surface.

D : Generalization : weathering force, dryness, contrast.

E: The interplay of whites and blacks. The blacks as a river covered with ice that is at thawing stage.

F : Black shadowy bat-like figures play over white.

G: The surface seems to have ominous patterns—perhaps of sharply silhouetted birds or bats. Blacks and whites.

H: Vague, eagle-like (Hapsburg Eagle) form.

The print of the Murphy picture was examined in the hand with free association encouraged. Only a summary of the response is necessary: It struck some persons as being fragile, a pale and beautiful thing, but pathetic. Others found it disturbing, even ghastly. Its location (probably in a Louisiana cemetery according to conjecture) the function of the object pictured (memorial ornament on a grave was the information generally accepted) the odd-angled shape of the frame (explained by someone as an attempt, perhaps, to avoid some reflections in the glass front of the case), the presence of reflections of crosses in the glass front and the pale tonality of the dove were noted. In free association several minor disgusting attributes were mentioned: a "gelatinous” eye, a "sentimental” bend of the neck, a "stuffed” quality of the dead animal. Some expressed a feeling of futility of this memorial gesture (a similar expression may sometimes be heard when one views a faded memorial wreath in a cemetery) . Paleness, fragility, weakness, helplessness, all these effects were felt. There was a real reluctance to come to grips with this image. Probably the heat and fatigue of an afternoon session contributed to this response.

In working with Dorothea Lange’s Three Women Walking, the general problems of interpretation were disclosed with exceptional precision — due partly because the image is so specific and the photographer’s intent is so "abstract.” The inferences were remarkable because of the consistency with which they fell close to the central point, yet somehow failed in rising to the correct abstract generalization.

A summary of this session will suffice: The three women were recognized as being different in age, dress, and in relative positions to one another. The younger was seen slightly in front and some took this to mean she was not "with” the others. Conjecture centered quite soon on the predicament of the oldest woman. Was she seeking something (perhaps that bit of white paper or card on the walk in front of her?) Was her expression one of grief? Was she returning from a hospital, a doctor’s office, a funeral? The presence of paper bags and the untroubled expression of the youngest woman contradicted that inference. Was the oldest woman a refugee just off the ship? (Several persons clung to this view.) All the central points were disclosed (as well as a number of irrelevant ones which merely established the scene) . Nevertheless, even with those who conjectured some relationship, even blood relationship, between these women, the central point intended was never mentioned. (It may have been suppressed by some of those present, but no claim was made for this even after Lange’s statement was read.)

A completely different group produced the following first statements : (The number of persons making similar statements is given at the right) :

People (three women) walking (on a street in a large city) ... 2

Three phases of woman’s life (youth, middle age, old age) ... 5

Three generations contrasted..........1

Stages of life (life in general shown in generations).....1

Youth ignores age.............1

Three types of shoppers...........1

Three types of city people...........1

Oneness of Humanity............1

Three different social types..........1

The young girl from "elite”

Mother from "middle class”

Grandmother from "lower class”

And as Richards says at the close of his remarkably apt book (again paraphrased to fit the present subject, pp. 328-329) : The critical reading of photography " is an arduous discipline; few exercises reveal to us more clearly the limitations under which, from moment to moment, we suffer. But, equally, the immense extension of our capacities that follows a summoning of our resources is made plain. The lesson of all criticism is that we have nothing to rely upon in making our choices but ourselves ...”

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Henry Holmes Smith

-

Photographs And Public

Winter 1953 -

Fredrick Sommer: Collages Of Found Objects / Six Photographs With Reactions By Several People.

Fall 1956 -

The Experience Of Photographs

Fall 1957 -

Exhibition Review

Exhibition ReviewThe Art Of Photography

Summer 1962 By Grace Mayer, Henry Holmes Smith, Hyatt Mayor, 2 more ... -

Concerning Significant Books

Concerning Significant BooksTwo For The Photojournalists

Winter 1960 By Henry Holmes Smith -

The Workshop Idea In Photography

Winter 1961 By Ruth Bernhard, Minor White, Ansel Adams, 2 more ...