THE MENTAL BASIS

In their essential nature men do not change. The great and noble, the Masters of Life, will be great and noble to the end of time, and to contemplate them and their deeds inspires us to endeavour to emulate them. Learn whom a man venerates, and you can come to judge his character. Like is assimilated unto like. The mind approaches that which it continually contemplates, and kindred acts inevitably follow.—Alvin Langdon Coburn1

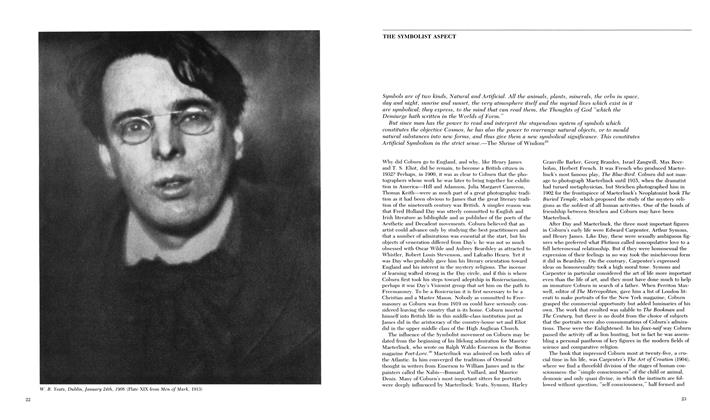

Alvin Langdon Coburn was born in Boston in 1882 into a solid middle-class family, but his father, a shirt manufacturer, died when the boy was only seven. This appears to have resulted in a degree of insecurity combined with indulgence that bound him too closely to his ambitious mother. (By his own admission, when his mother remarried he gave his stepfather considerable annoyance.) In 1890, the year after his father died, he visited his uncles in Los Angeles, and they gave him a Kodak. Much more significant was the gift that his distant cousin Fred Holland Day, the bibliophile, publisher, and photographer, made him in 1901—a copy of Chambers Dictionary.2

Coburn had crossed the Atlantic in 1899 with his mother to take rooms at 89 Guilford Street, Russell Square, London. Day was in Mortimer Street not far off, having brought over from the United States a huge selection of American photographs for exhibition at the Royal Photographic Society. There were one hundred three photographs by him, twenty-one by Edward Steichen, and nine by Coburn. Alfred Stieglitz had refused to take part, as there was rivalry and mistrust between him and Day. Mrs. Coburn’s jealousy of Steichen failed to damage Steichen and Coburn’s relationship, although it harmed Coburn in Stieglitz’s eyes. Coburn studied in Paris with Steichen and Robert Demachy in 1901 before he and his mother went off on a tour of France, Switzerland, and Germany.

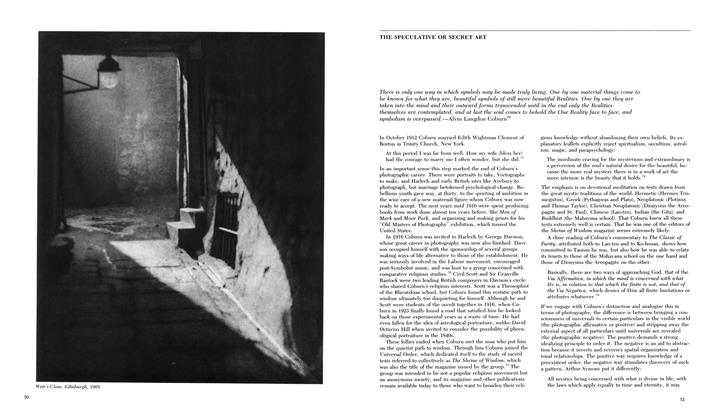

In 1900 Coburn had also exhibited with the Linked Ring Brotherhood, founded in 1892 by a group of photographers that included H. P. Robinson, George Davison, and H. H. H. Cameron, Julia Margaret Cameron’s son. The three interlinked rings that were the symbol of the Brotherhood had Masonic overtones and probably referred to the triadic virtues of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. (In 1927, when Coburn was made an honorary Ovate of the Welsh Gorsedd, or meeting of Druids, he took the Welsh name Maby-y-Trioedd, “son of the triads. ”) In 1900 too Coburn met Frederick H. Evans, the British photographer of cathedral interiors, who was also a “Link. ” It has recently been shown that Evans was a Swedenborgian like Henry James Sr., whose writings he admired.3 Connections between European and American comparative religious thought were firmly established through Emerson, Whitman, Maeterlinck, and the James family. Coburn’s later mentors, Edward Carpenter, Arthur Symons, and Henry James Jr. (the novelist), sustained this mental basis for him but also weaned him from the Decadent influence of Fred Holland Day. That influence was probably more innocent than diabolical, and Coburn probably remained too boyish to fall wholly under his cousin’s spell— there is no sign of homoeroticism in Coburn’s work. He seems to have been more influenced by Day’s maternal imagery than anything else.4

In 1902 Coburn opened a studio at 384 Fifth Avenue, New York, and studied with that great Madonna figure in the history of photography, Gertrude Käsebier. She probably encouraged his attendance at Arthur Wesley Dow’s summer school in Ipswich, Massachusetts, which gave him the grounding in composition that was to underpin his own contribution to photography. But his conception of the craftsmanly ideal brought him back to London in 1904 to join Frank Brangwyn, an inheritor of the William Morris tradition. Through Frederick Evans he met George Bernard Shaw, and in the annus mirabilis of 1905 he got to know Henry James, Edward Carpenter, and Arthur Symons.

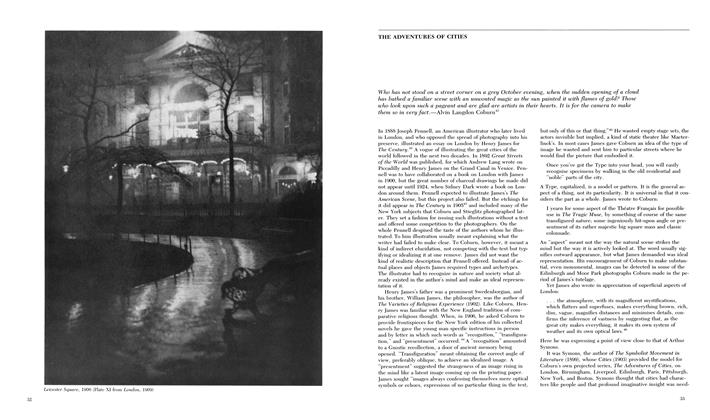

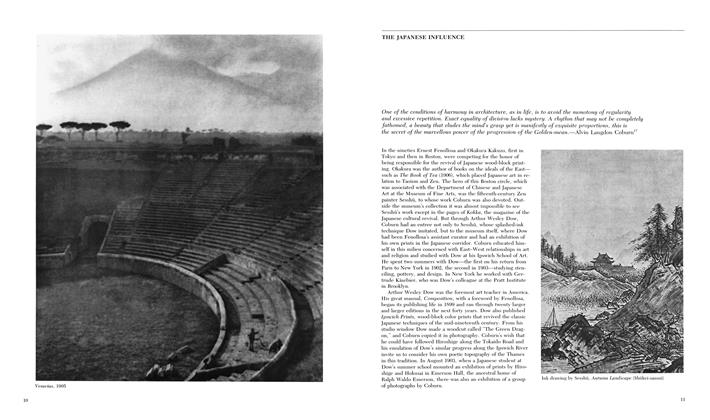

It is extraordinary how attracted—and attractive—Coburn was to his seniors. In 1907, when Shaw considered the twentyfour-year-old Coburn the greatest photographer in the world, Maeterlinck, Symons, Brangwyn, Stieglitz, and Day were in their forties, Shaw and Dow in their fifties, and James and Carpenter in their sixties. Coburn’s sensibility was formed by people at least a generation older than himself, artists who had direct links with Aestheticism (Maeterlinck and Day), the Symbolist movement (James and Symons), and the socialism of William Morris and Ford Madox Brown (Carpenter and Brangwyn). Coburn was full of energy and ambition, so much so that his nickname in the Linked Ring, to which he had been elected in 1903, was “The Hustler.” In 1906 he took up the study of photogravure and went to Paris, Rome, and Venice to work on the frontispieces for the New York edition of Henry James’s novels. His travels continued to New York and Detroit in 1907 and Ireland, Holland, and Bavaria in 1908. In 1909 he set up presses in Hammersmith, London, to print his own photogravures for his London and New York portfolios.

In 1908, however, there had been some tart personal criticism of him in Camera Work:

Coburn has been a favored child throughout his career. Of independent means, he launched into photography at the age of eight. Gradually, and to the practical exclusion of everything else, he devoted all of his time to its study. Originally guided by his distant relative, Holland Day, he, at one time or another, at home or abroad—the Coburns, mother and son, were ever great travelers—came under the influence of Käsebier, Steichen, Demachy, and other leading photographers. Instinctively benefiting from these associations he readily absorbed what impressed itself upon his artistic self. Through untiring work, and urged on by his wonderfully ambitious and self-sacrificing mother, his climb up the ladder was certain and quick. Arriving, three years ago, in London, for a prolonged stay there, his sudden jump into fame through the friendship of Bernard Shaw is well known. Shaw’s summing up of Coburn can be found in Camera Work, Number XV. No other photographer has been so extensively exploited nor so generally eulogized. He enjoys it all; is amused at the conflicting opinions about him and his work, and, like all strong individualities, is conscious that he knows best what he wants and what he is driving at. Being talked about is his only recreation.5

The author was probably Alfred Stieglitz. Coburn evidently thought so when he wrote to him in plaintive terms, not so much on his own behalf as to say that his mother (who was not too well, he said) had been upset by it.6 The sly insinuation of the piece, which rose to heights of sarcasm to end in hollow eulogy, had, Coburn appeared to suggest, not touched the victim himself. Mrs. Coburn had trumpeted her son’s work on every possible occasion, and Stieglitz evidently considered him a mother’s boy. But perhaps what rankled most with Stieglitz was Coburn’s alternative promotion of photography in Britain, including a new portfolio club, The Brotherhood, with George Davison, James Craig Annan, Baron de Meyer, and others. Although Coburn was always careful to see that Stieglitz was included in the British publications in which he had some influence, such as the Studio special issue Art in Photography (1905) and A. J. Anderson’s The Artistic Side of Photography (1910), it would have been quite apparent to Stieglitz that Coburn was refusing to confront him while managing to keep his complete independence.

However, Coburn’s conduct over the introduction of the Lumière Autochrome into Photo-Secessionist circles does seem to have been somewhat underhand. Having learned how to simplify the process in Steichen’s darkroom in Paris while Stieglitz was present, Coburn jumped the gun by giving an interview to the press on color photography before Stieglitz could get back to America to call a press conference himself. ' In an interview, Coburn gave the impression that he was the sole person qualified to use the new process. He did mention Frank Eugene and Steichen, but that would have only enraged Stieglitz further because he was the one who had initiated Eugene in Autochrome work. Coburn was something of a hustler, after all. From a more tolerant point of view, he was only twenty-six years old and still did not know how to behave. The young man with the Latin Quarter beard appeared opinionated, facetious, and overconfident, whereas he was really emotionally very immature. How could Shaw have described him as a “specially white youth,” and Stieglitz as “tricky”?8 Well, he was divided in himself between altruism and ambition—not so uncommon at that age.

Coburn’s essential nature had yet to be clearly brought out from under the pressures of immaturity and precociousness. In 1904, when Coburn was only twenty-two, J. B. Kerfoot, one of the editors of Camera Work, caricatured him as young Parisfal, “pouting because the Holy Grail eludes him.”9 Sadakichi Hartmann, the greatest of all photography critics, remarked on the physical resemblance between Coburn and Emmanuel Signoret, editor of the Symbolist magazine Le Saint-Graal (1892-99).10 The quest for religious truth implied in pursuit of the Grail was firmly attached to people’s idea of Coburn. They saw him as a holy innocent, somewhat spoiled by his mother. In short, the ethical basis of his life was not yet developed—social acts kindred with his high ideals had not yet followed in the wake of his status as an infant prodigy.

Coburn shared the same difficulties as two or three previous generations of Americans. It seemed to them that there was not much in American society to help them mature as human beings, and so they went to Europe. Once there, T. S. Eliot turned to the Anglican Church for spiritual help, and Ezra Pound looked to systems of education. Coburn turned to the orders of chivalry in his pursuit of the Holy Grail, and, after 1919, to Freemasonry, which was the logical extension in the British context. The local people who knew him in North Wales in the forties saw him as a stalwart of the local dramatic society in Harlech, as an active Freemason, and as Head Store-Keeper of the Joint County Committee of the Red Cross Society and St. John Ambulance who turned his house into a fifteen-bed hospital during the war. It is very hard to recognize as the same person the young man in the Whistlerian top hat and the vegetarian who kept goats and whose hobbies were walking, cycling, and gardening.

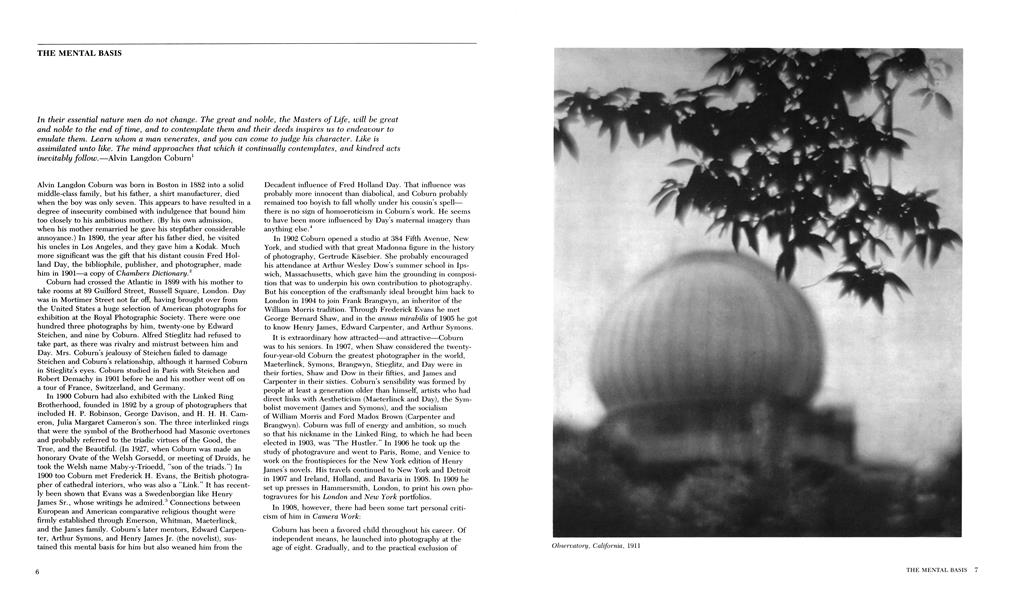

The mental basis of Coburn’s life was committed to hidden or ideal philosophy from his beginnings as a “young Parsifal” in 1904 to his Grand Stewardship of England in the Allied Degrees of Masonry in 1930. But it is possible to identify certain phases in his life as of special significance. The years 1900—1905 were his apprenticeship; 1905—10 was his Symbolist period, in which he made his great contribution to photography; 1916—23—years that Coburn himself described as wasted—saw him in confusion, dabbling in astrology and the occult; 1923-30 was the period when he became completely devoted to the life of the Universal Order, a comparative religious group that had begun in 1911 as the Hermetic Truth Society and the Order of Ancient Wisdom. Its quarterly magazine, The Shrine of Wisdom, began publication in 1919, the same year Coburn became a Mason. To read this magazine over a nearly thirty-year period is to get a very clear idea of Coburn’s beliefs.11 The man who changed his life from 1923 on was the unnamed leader of the group,12 and Coburn’s solidity as a citizen and the falling-away of all mundane ambition thereafter was due to his direct influence. The Universal Order provided the background for activities as a Rosicrucian, a Druid, and a Freemason. Coburn had added Druidism, the Welsh religion, to his interests as early as 1916, when his visits to George Davison, the photographer and philanthropist, in Harlech had introduced him to the composers Sir Granville Bantock, who shared his Druidical interests, and Cyril Scott, who was an active Theosophist. Coburn toured the great megalithic sites of Stonehenge, Glastonbury, and Avebury in 1924 and photographed the stone circles in 1937. His interest in ancient British religion was constant over a long period. In 1938 he wrote a play, Fairy Gold, with music by Bantock, which was Druidical in spirit but modeled on the Belgian mystic Maurice Maeterlinck's play The Blue-Bird (1909), which Coburn greatly admired. His interest in Freemasonry predated his initiation in 1919-the fifty books by A. E. Waite on his shelves covered a range of interests from the Holy Grail to the history of the Ma sonic and Rosicrucian orders. Waite's introduction to a little German work, The Cloud upon the Sanctuary,'3 may have been as influential on Coburn's cloud photographs as Yoné Noguchi's book The Summer Cloud (1906). So far as Coburn was con cerned there was no difficulty in embracing East and West, an cient and modern, simultaneously. In 1927 he became a Druid; in 1928 he began his long study of the Chinese Taoist classics in the British Museum Library; in 1935 he became a lay reader in the Anglican Church in Wales; and by the forties he was a pro lific speaker and writer on Masonic subjects.

It is possible to see 1928-30 as watershed years. Coburn’s mother died; he lost all his beloved Pianola rolls in a flood; he gave his collection of photographs to the Royal Photographic Society, destroyed fifteen thousand negatives, and moved from London to North Wales. In 1930 he was still only forty-eight, but his life from beginning to end was one of overlapping circles of interest linked forward and backward simultaneously; his basic inclinations never changed, only the external conditions.

External conditions are, however, crucial in the accurate description of Coburn’s contribution to photography. What makes him a great photographer is that his Symbolist period, 1905-10, provided him with the four factors necessary to a photographer who wished to advance the art: the philosophical basis (comparative religion), the aesthetic basis (Japanese art), the technical ba'sis (the telephoto lens and the soft-focus lens), and the craftsmanly basis (photogravure). Such factors determine the contribution of any great photographer (for example, for Julia Margaret Cameron the bases were Christianity, Dutch and Italian art, the selective-focus lens, and the albumen print). The mental basis of the photographer may not change, but the conditions under which he or she works do. There is the moment when everything comes together, which then passes. Most artists do not survive the moment as artists. Only those of extraordinary capacity to adapt to new conditions have several such creative moments. These are artists of genius like Stieglitz, Steichen, and Paul Strand. The merely great artists have only one such period: Julia Margaret Cameron (1864—74), Frederick Evans (1900-1911), Edward Weston (1927-37). Coburn, like them, had one (1905-10, extendable to include the Yosemite and Grand Canyon pictures). Then he got married, returned to England, and photographed only intermittently.

To include the month-long Vorticist instant of his career is logical from the modernist historian’s point of view. In January 1917, under the influence of London’s response to Cubo-Futurism, Coburn lashed together three of Ezra Pound’s shaving mirrors, rigged them below a kind of glass lighttable, and produced his Vortographs. These have taken their place in the history of abstract photography with Man Ray’s Rayographs, Christian Schad’s Schadographs, and the light experiments of MoholyNagy. That Coburn’s kaleidoscopic efforts preceded those of others by a year or two has tended to propose his significance to the history of photography as an avant-gardist and early modernist, when in fact his major contribution was symbolist and impressionist. By 1917 external conditions had changed dramatically: modernism, optical experiment, and bromide papers had succeeded japonisme, Symbolism, soft-focus lenses, and photogravure and put Coburn out of step. Steichen’s response to the crisis of modernism was different. He turned to studies of forms in nature under the influence of Theodore Andrea Cook, the English morphologist,14 whereas Coburn was sucked briefly into the Cubo-Futurist vortex.

Coburn’s taste in music enshrined Wagner and Sibelius, but he asked himself whether there was a future for him alongside Stravinsky and Schoenberg as he himself began to punch abstract patterns into a Pianola-roll-cutting machine to see what came out:

Yes, if we are alive to the spirit of our time it is these moderns who interest us. They are striving, reaching out towards the future, analysing the mossy structure of the past, and building afresh, in colour and sound and grammatical construction, the scintillating vision of their minds; and being interested particularly in photography, it has occurred to me, why should not the camera also throw off the shackles of conventional representation and attempt something fresh and untried? Why should not its subtle rapidity be utilised to study movement? Why not repeated successive exposures of an object in motion on the same plate? Why should not perspective be studied from angles hitherto neglected or unobserved? Why, I ask you earnestly, need we go on making commonplace little exposures of subjects that may be sorted into groups of landscapes, portraits, and figure studies? Think of the joy of doing something which it would be impossible to classify, or to tell which was the top and which the bottom!15

Of course a modernist camera vision can abnegate reality, indulge a desire to manipulate reality, destroy perspective altogether, and discard traditional genre subjects, but the joy of losing all orientation with regard to human reality is ultimately illusory and sterile. It is especially perverse when the camera and film and photographic paper, the most efficient combination in the rendering of realistic surfaces, are used to fulfill a modernist commitment to abstraction.

When a young person, spiritually alive but not consciously enlightened, approaches the phenomenal world without studying it so much as intuitively responding to it, the making of art is always possible. But when this same person becomes a fully trained mystic the manifested universe is seen in increasingly ideal terms—as material for a science of ideas rather than an art of symbols. In order to remain an artist this person must not pass so quickly from the visible to the invisible world that there is no physical sign left to commemorate the adventure with mundane reality.16

The approach taken in this essay focuses on Coburn’s Symbolist period, when he considered art neither entirely naturalistic nor wholly abstract but generally symbolic.