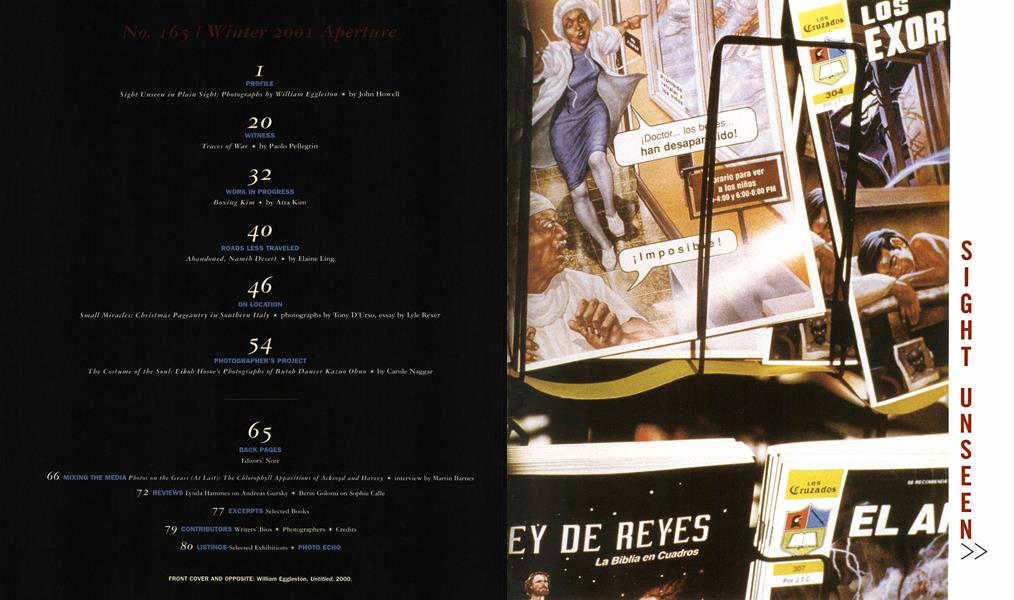

SIGHT UNSEEN IN PLAIN SIGHT

PROFILE

JOHN HOWELL

The first time I saw William Eggleston, he didn't see me. It was the mid sixties, in Memphis, his hometown, where I was a college student. The places were the Beatnik Manor and the Bitter Lemon, the midcity ground zero of bohemian Memphis. The Manor, a run-down old house, was a crash pad and after-hours party spot, and the nearby Bitter Lemon (opened and run by Manor dwellers) was first a folk, then a psychedelic ice-cream parlor, coffeehouse, and art gallery. This ad hoc cultural complex was the 24/7 laboratory for the Memphis version of sixties counterculture. And a motley crew it was: bearded art-school teachers and long-haired students, preppie slummers (like myself) and runaways, big bikers and exotic dancers, old black blues singers and young white folk singers, Yankee culture-mongers and drug-addled drifters. What this poly glot crowd shared was a desire to be different in response to seriously changing times. (Dylan had played Memphis by then.) We didn't know it then, but we were deculturalizing.

At the time, I was a wide-eyed, eighteen-year-old voyeur, fas cinated enough to visit but spooked enough to stand back from the action. I was there, but kept myself invisible. In the midst of this scene, a very visible man appeared one night in a tradi tional Southern white suit, iconic in his impeccable Delta cotton planter style. As the evening went on, it became clear that this improbable figure was perhaps the freest spirit in a psychic free zone filled with many others working very hard for that status. “Who,” I recall asking someone, “is that?” “Bill Eggleston,” was the answer. “He takes pictures.”

(continued on page 7)

(continued from page 2)

The second time I saw Eggleston, in 1989, he didn’t see me— or anyone really, because he wasn’t looking. About twenty minutes into Great Balls of Fire, the bio-pic about rock madman Jerry Lee Lewis, there’s an at-home moment where Lewis’s relatives gather around the piano to admire his playing.

Peeking over the heads of several extras in the brief scene is Eggleston (a friend of Jim McBride, the director), dressed in a fifties argyle sweater-vest and looking like Mr. Rogers’s weirder twin. Everyone in this basic reaction shot looks down, toward the piano; Eggleston alone turns his head to his right and looks away. Then, a couple of minutes later, Alec Baldwin (as Lewis’s cousin/evangelist Jimmy Swaggart) and Dennis Quaid (as Lewis) argue about God, the Devil, and rock ’n’ roll. Perfectly framed between them, seated on a chair in front of a window, with white crepe curtains above his head—floating above it like a celestial shroud—sits Eggleston, his eyes closed as if in private reverie. His presence is centered in the shot but he’s a sunken figure, seen at waist level behind the two principals, a ghostly one-man chorus, elevating the ersatz theological debate to its properly Manichean heights by his silent, unseeing witness.

Over the years, as I lived in New York and moved in art circles, I followed Eggleston’s career as it exploded into sight with the now-legendary 1976 Museum of Modern Art show of “perfect” (according to then-curator John Szarkowski) color photography, and kept up with his work through the infrequent but always revelatory gallery shows that followed. I also learned more about Eggleston the man from the official biographies, as well as scraps of Memphis gossip. I learned that he was the only son of an upper-class Mississippi Delta family (born in 1939). That he was ill-educated formally but a formidable autodidact, who had taught himself classical music and jazz, video filmmaking and photography (inspired at an early age by his discovery of Cartier-Bresson). That he was a gadget man attracted to anything mechanical: synthesizers, Sony portapacks, guns, cars, stereo systems. That he had an outsize reputation as a major league carouser, Southern-style, subcategory Mississippi Delta division (a very major carousing category, indeed). That he worked constantly, traveled widely, and had a range of bohemian acquaintances of astonishing variety (from avant international jet-setter Charles Henri Ford to polymath musician and artist David Byrne). Eggleston comes down these portentous stairs to greet me. He is dressed in the classic Memphis gentry uniform: blue pinstriped button-down shirt, khaki pants, and loafers. After saying hello, he settles on a stuffed chair, arranges his cigarettes and lighter, then sits, silently, smoking. He looks around the room as if checking for the exits. Like all Southerners meeting for the first time, I start the ritual of getting acquainted by matching up mutual friends, if not actual relatives. I give him Byrne’s new CD, Look Into the Eyeball. Eggleston’s photos were printed in the book about Byrne’s 1986 feature film, True Stories, and his supersaturated color and “democratic” vision were major influences on the movie’s look. I mention that I interviewed Byrne at the time of the movie’s release for a magazine article. Eggleston plays with the CD’s trick cover, which, when tilted back and forth, makes Byrne’s eyes open and close. Then he says, “David’s so original. . . . How is he? I run into him all over the world. Last time was in Naples. Met him in the hotel, in the hallway. . . .” The tale, whatever it is, trails off into silence.

Now, at my request on behalf of Aperture, I am invited to Eggleston’s Memphis home. Our meeting has been billed as “a visit,” the best way to get the famously shy and elusive photographer to meet to talk about his art.

I am met in the driveway of one of those 1920s neo-ltalianvi I la-style houses so in vogue among the Southern well-to-do of that era, by Eggleston’s wife of forty years, Rosa. She invites me into the house by the back door. (Is it only Southerners who build large houses with grandiose porticos and formal entry halls that are hardly used?) I am shown into the two-story living room.

There’s a coffee table piled high with stacks of snapshots, back issues of Artforum, and random correspondence. At one end doors open onto a music room. At the other end is a grand stairway illuminated by stained-glass windows that leads upstairs.

Eggleston smokes, looking into the far end of the room, out the windows to the trees beyond. I decide to go for what I know to be the Big Question for Eggleston: just how Southern does he think his work is?

His initial answer is a snort.

I ask about the parade of curators and journalists—almost all of them from outside the South—who have shown up over the years and who, echoing Faulkner’s interrogators {“Tell us about the South”), query Eggleston about the Meaning of the South.

He just shakes his head. “I don’t know what they’re looking for. I don’t have any idea.”

The issue of Southern Significance has stuck to Eggleston like pancake batter on a too-hot skillet. As if kudzu-covered rusty pickup trucks, ramshackle buildings, and hard-eyed women in harder-looking beehive hairdos carry a declamatory symbolism that requires elaborate cultural analysis, much of it mournful in tone and eulogistic in conclusion. “Southern” always strikes Southerners as a condescending tag. It’s taken to mean “regional,” as in local, anecdotal, folkloric, and outrageously melodramatic—in other words, like those all novels, films, and plays full of enervated aristocrats, trampy women, and idiot men—children acting out in bizarre ways. It’s as if solemn phrases about the drama of the decaying South soothe those puzzled by Eggleston’s pictures (“What are they about?”), and those—mostly now in the past—outraged by the “banal” subject matter.

Eggleston gives his consistent philosophic answer: “You can take a good picture of anything. A bad one, too,” he adds, with a chuckle. He has said many times that the subjects of his pictures were simply an excuse to make photographs. “I want to make a picture that could stand on its own, regardless of what it was a picture of. I have never been a bit interested in the fact that this was a picture of a blues musician or a street corner or something.”

While there are several ways to think about that stance, perhaps the most important is the one in plain sight: Eggleston is trying to direct his—and by extension, the viewers’—attention to the act of seeing, to angles of vision in looking at the world and the things and people in it. He has spoken of wanting to use the vantage points of an insect and of a child to take pictures (as in his close-to-the-ground view of a tricycle that is the cover of Eggleston’s Guide, the catalogue for the momentous MoMA show). He has talked of shooting with the camera the way a duck hunter uses a shotgun, lifting, aiming, and following through in a full-body glide to lead the target. He has shot without looking through the viewfinder. He usually limits himself to taking one picture per subject (no bracketing for exposure, no refocusing). For Eggleston, photography is actively seeing, both literally and metaphorically. Grandiose subjects are like large conclusions: they are not usually in sight. Decisive moments are instants that occur in swarms of millions, fractional instants pulled out of the unending stream of phenomena and activity by scanning what’s out there and clicking the shutter. What’s “ordinary” subject matter, anyway? Eggleston’s pictures ask. Doesn’t life consist largely of everyday rooms, basic objects, and familiar people? And can’t those be made mysterious and wonderful and ominous and funny in their own right by a certain way of looking at them?

The question of angle of vision comes up when his son Winston, who manages Eggleston’s business affairs and archives, drops by with prints from the latest Cheim & Read show for the photographer to sign. (Eggleston has another grown son, William Jr., and a daughter, Andra.) As Winston carefully unwraps the prints and puts them before Eggleston, there’s a problem. It’s that photo of a pink sink: which way does the picture go, vertical or horizontal? I realize that the man who took the picture ... is not sure. Winston puts it on the table as a vertical, which is how it has been printed, he says, in a book published by the Fondation Cartier, but now he observes, “Look at that shadow. This should be horizontal.” I realize that the confusion exists because the angle from which Eggleston chose to photograph the sink is so unusual—it is as if you are looking at the sink in a way you never have, and the mind cannot organize the image. The “wrong” way, vertically, makes more “sense.”

Eggleston asks me what I think. I tell him. I add that the horizontal, correct way to view the picture is a “vertiginous” one. It makes me dizzy. “What’s that word? Vertiginous? I’ll have to remember that one. . . .” Then he signs the prints as horizontals.

The next print that comes out of the box is Red Jesus. “That’s not immersed in blood, is it?” I ask. “And is it in a cemetery? Red dead bloody Jesus?”

Eggleston chuckles. “It’s my version of the Piss Christ,” he says. “That ought to shake ’em up.”

I say I think it will take a lot more these days to make a scandal with a heretical photograph than it used to. “How about Satanic Jesus then?” Eggleston replies.

I say nothing, hoping to myself that this never gets around in Memphis. Satanic Jesus would indeed just about do the job, I think.

The prints are departures in several ways for Eggleston: they’re Iris prints instead of his standard dye-transfer process, and a new, larger size, 24 by 30 inches. With more muted colors and a larger area for the eye to move over, they seem even more mystifying. They oscillate harder between abstraction and realism, sincerity and irony, symbolic meaning and anecdotal charm.

There’s a Zen-like emptiness at their center—you have to look around in the picture, slowly, to begin to get it. While this experience in Eggleston’s most recent work is different, overall the feeling is ultimately the same one always conjured up by his distinctive, disjunctive, Eggleston way of looking at what’s out there. The same but different—that’s the clue to an artist with a vision who is still extending it, exploring.

The same is true of the recent snapshots taken in San Diego and Tijuana, which Eggleston allows me to look through. Flipping through an unedited pile of drugstore-processed pictures, you discover two things: how remarkably consistent his vision is— even snaps look like “Egglestons”—and, at the same time, how that vision tries to see something unique in its sighting on each subject, whether parking lot or python. One way is technical: when I ask what these photographs were taken with, Eggleston answers, “One-third with a Leica, one-third with a Contax, and one-third with a Pentax.” This gadget man is always tinkering with the tools of reproduction. Another is the subject matter: “Walter Hopps, an old friend of mine, suggested that I go to the world-famous San Diego zoo, so I did. It was horrible, just like Disneyland.” And Tijuana? “I only stayed ten minutes. It never rains there, but it did when I hit town—a complete flood. Had to leave as soon as I got there.” Yet despite these misadventures, there’s a huge stack of photographs, proving that a determined visionary can indeed make a picture of “anything.” Another Zen thought occurs to me: there are no accidents.

Eggleston is also known for making music much in the same way he takes photographs. The self-taught keyboardist improvises, records everything in the first take, and does not edit the results. He invites me into the music room where there’s a harpsichord, an Eggleston-designed and built stereo system, and a synthesizer. The amplifiers rest on Winchester shotgun-shell-ammo boxes. The bookshelf overhead contains rows of contrasting titles: one trio of adjacent books—Velikovsky’s Worlds in Collision next to The Better Homes and Gardens Sewing Book, flanked by The Great Century of the Gun—makes a symbolic mini-portrait of Eggleston’s interests and influences.

He inserts a disk into the synthesizer, and the music that pours out of the speakers is many things at once: New Age ambient, church-like hymnal, funeral-home dirge, Bach-like counterpoint, and jazzy improvisation, with occasional threads of pop music melodic themes. Much like the polymorphous perversity of the vision that informs his pictures, Eggleston’s “democratic” compositions have the effect of being both stimulating and soothing at the same time, with their hybrid blend of sound.

(continued on page 64)

(continued from page 18)

While listening, I reflect that I have been invited in through the back door, served iced tea and invited to stay for lunch, shown pictures of Jesus—and now am hearing the Eggleston version of “Old Man River” emerge from his speakers. Just as when looking at his pictures, I am definitely in the South—but not just the South. I am in Eggleston’s world, where what’s at hand is used as a given vocabulary to create something previously unseen: a world full of surprising collisions, located somewhere between the ideas of home and the gun. That world is on view in other pictures taken by Eggleston in Kenya and London, in the Arizona desert and the heart of Berlin, as well as in Memphis.

If the perfect relationship is, as the country song has it, “somewhere between lust and watching TV,” for Eggleston, the perfect picture is something with lust and watching TV— and a dozen or more other attitudes—in it. His appetite, and his willingness to share it through his photography, enlarges our own. ©

An exhibition of William Eggleston ’s work, curated by M. Hervé Chandès, Director of the Fondation Cartier, is being held at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, November 18, 2001-February 17, 2002.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

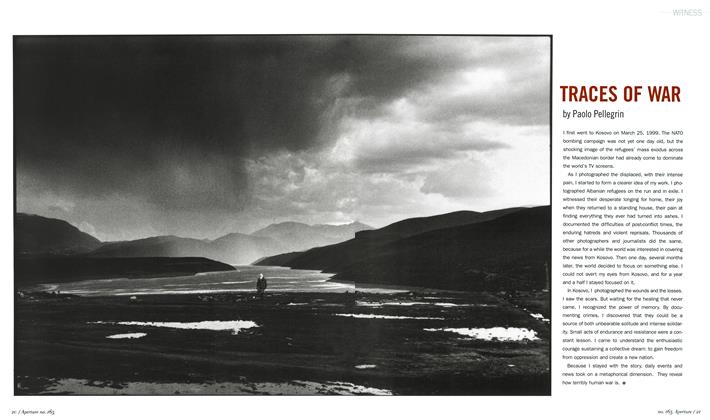

Witness

WitnessTraces Of War

Winter 2001 By Paolo Pellegrin -

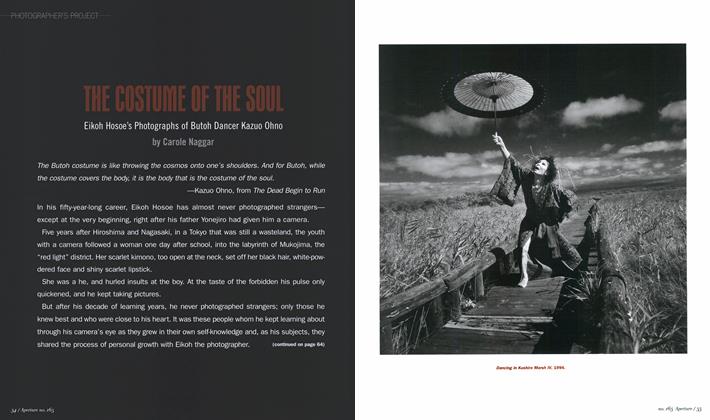

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectThe Costume Of The Soul

Winter 2001 By Carole Naggar -

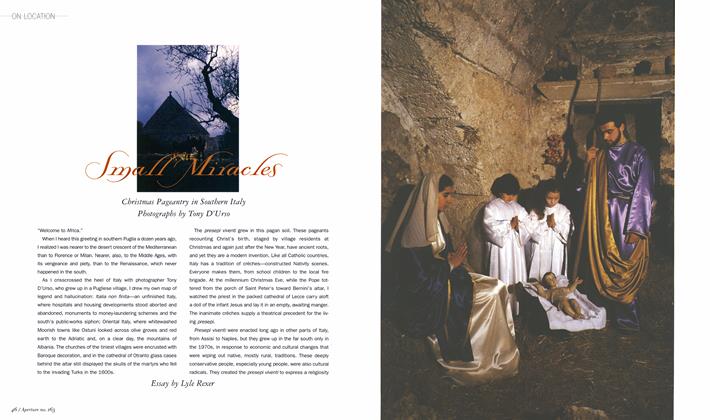

On Location

On LocationSmall Miracles

Winter 2001 By Lyle Rexer -

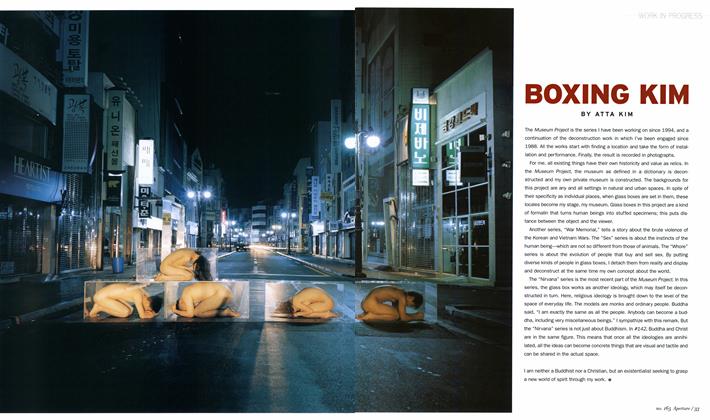

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressBoxing Kim

Winter 2001 By Atta Kim -

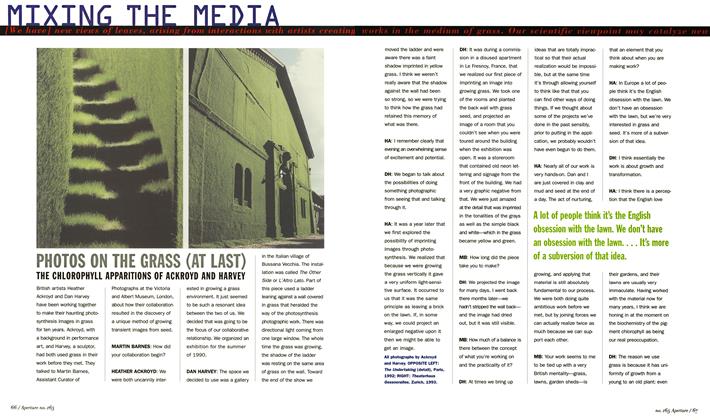

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaPhotos On The Grass (at Last)

Winter 2001 -

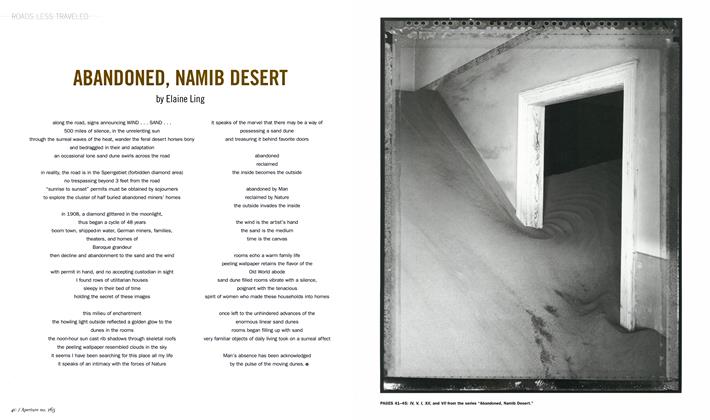

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledAbandoned, Namib Desert

Winter 2001 By Elaine Ling

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

John Howell

-

Reviews

ReviewsChic Clicks

Spring 2003 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsArtist To Icon: Early Photographs Of Elvis, Dylan, And The Beatles

Winter 2005 By John Howell -

Books

BooksThe Ongoing Moment

Summer 2006 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsMississippi Delta Photography

Fall 2007 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsRichard Prince: Spiritual America

Spring 2008 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsLincoln Center: Celebrating 50 Years

Fall 2010 By John Howell

Profile

-

Profile

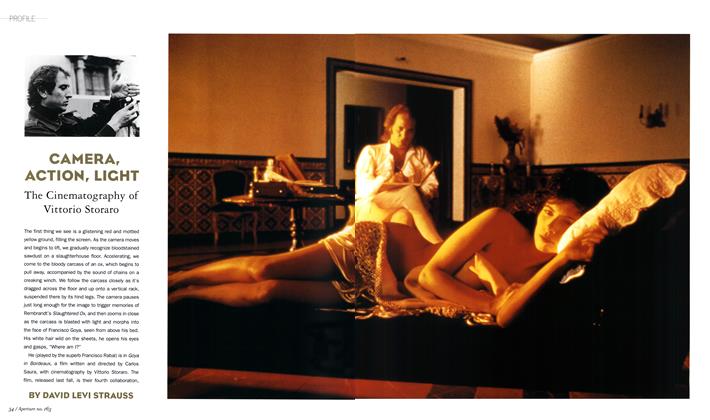

ProfileCamera, Action, Light

Spring 2001 By David Levi Strauss -

Profile

ProfileElinor Carucci’s Theater Of Intimacy

Spring 2006 By Diana C. Stoll -

Profile

ProfileRe-Inventing The Spaces Within: The Images Of Lalla Essaydi

Spring 2005 By Isolde Brielmaier -

Profile

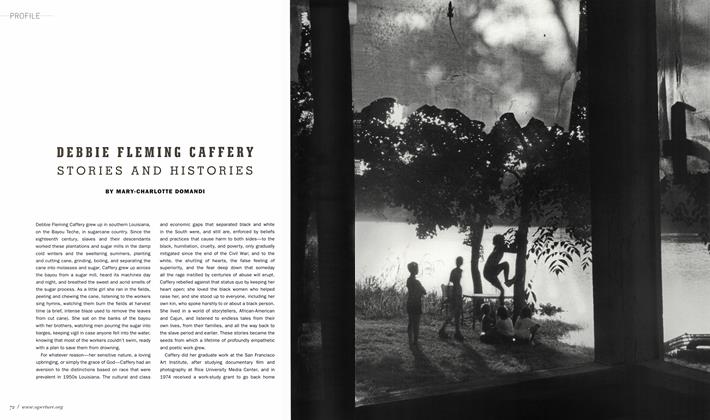

ProfileDebbie Fleming Caffery Stories And Histories

Fall 2009 By Mary-Charlotte Domandi -

Profile

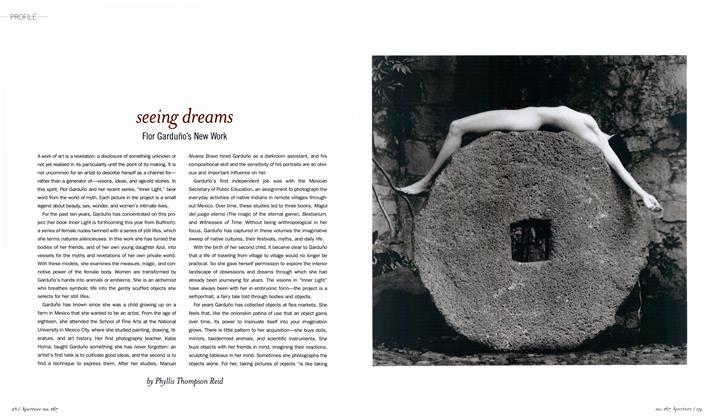

ProfileSeeing Dreams

Summer 2002 By Phyllis Thompson Reid -

Profile

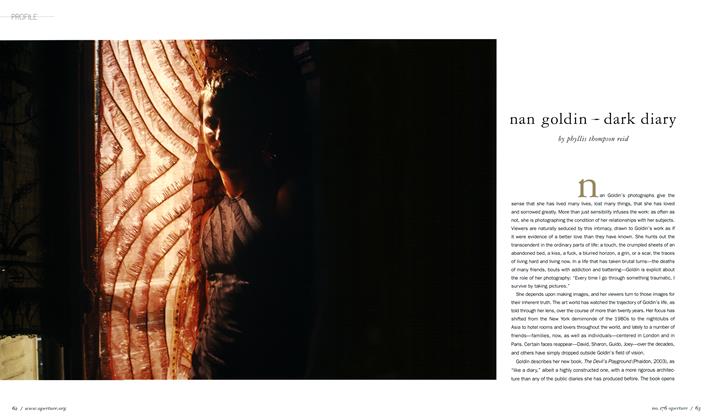

ProfileNan Goldin — Dark Diary

Fall 2004 By Phyllis Thompson Reid