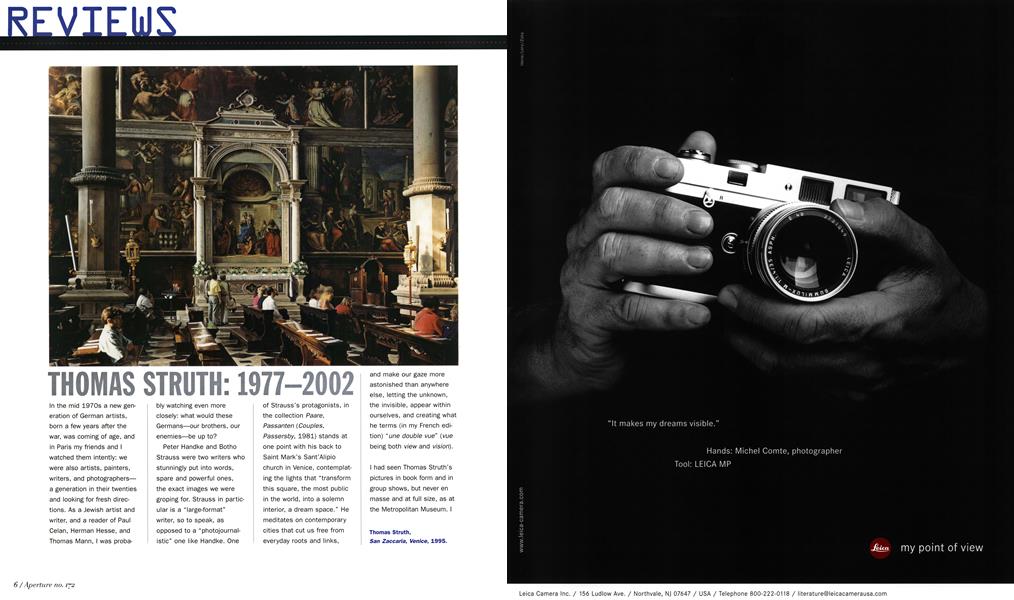

THOMAS STRUTH: 1977-2002

REVIEWS

In the mid 1970s a new generation of German artists, born a few years after the war, was coming of age, and in Paris my friends and I watched them intently: we were also artists, painters, writers, and photographers— a generation in their twenties and looking for fresh directions. As a Jewish artist and writer, and a reader of Paul Celan, Herman Hesse, and Thomas Mann, I was proba-

h v w~tr~hip~ w~n mnrf~ C osely: wnat wouia tnese Germans-our brothers, our enemies-be up to?

Peter Handke and Botho Strauss were two writers who stunningly put into words, spare and powerful ones, the exact images we were groping for. Strauss in partic ular is a "large-format" writer, so to speak, as opposed to a "photojournal istic" one like Handke. One

nj~jjic~c~ r~rr~t~1mj.Qj~. `? tM 8ii~ti6h i-'aare, Passanten (Couples, Passersby, 1981) stands at one point with his back to Saint Mark's Sant'Alipio church in Venice, contemplat ing the lights that "transform this square, the most public in the world, into a solemn interior, a dream space." He meditates on contemporary cities that cut us free from everyday roots and links,

and make our gaze more astonished than anywhere else, letting the unknown, t}~J~E' 1~i~}~i he terms (in my French edi tion) une double vue" (vue being both view and vision).

I had seen Thomas Struth's pictures in book form and in group shows, but never en masse and at full size, as at the Metropolitan Museum. I had always thought of them as the images for Strauss’s and Handke’s books—as their missing illustrations. While Struth is often commended for his precision and realism, his work to me had the “realism” of dreams. Sadly, the exhibition “Thomas Struth: 1977-2002” not only led me to abandon this interpretation, but changed my understanding of his work irrevocably.

At first, there is a seductive game that one can play with Struth’s black-and-white streetscapes: they demonstrate that time passes at different speeds in different parts of the world, and even sometimes in the same spot. One can place them: 1978 in both Manhattan and Naples looks somehow like the 1930s. Shanghai, photographed in color in 2002, looks like the 1970s. Tokyo in 1991 looks like William Klein’s “Hollywood by Light,” shot in the 1960s, except for the London Sunday Times magazine-like colors, both vivid and faded. Venice’s Calle Tintoretto will always look like the seventeenth century, while Duittenburg in 1991 looks exactly like the late 1940s.

But this variable-time effect does not derive solely from architecture, nor does it apply solely to Struth’s streetscapes. We discover it again and again throughout his work: in his portraits— both the individual video depictions and the unsmiling family portraits—as well as in his famous, outsized views of museums interiors, Chartres Cathedral, Notre Dame, and so on. But this game is only a game, and rarely does it open the dream passage to a “double vue."

Since this is America, where big is beautiful, Struth’s gigantic photographs are the ones that generally garner the most attention. Museumgoers are drawn to them and remain glued before them. They lose whatever sophistication they might have had and become like those tourists for whom the 1950s is ancient history, gawking at the portal of a medieval cathedral (“Really! And they built it by hand!

And it took two hundred years]”). Some viewers show their children: “Look: this is where we were in Paris” (or in Rome, or right here at the Metropolitan’s own reconstructed Temple of Dendur). Perhaps they are hoping to find themselves among the swarms of tiny photographed tourists that crowd Struth’s photographed sites.

Like most photographers, Struth is seeking an excuse to do exactly what our parents told us not to do, and what all tourists—in a coded, specific way—are given license to do: to stare with impunity at famous places or at total strangers. He does it well. Nonetheless, I cannot follow his many commentators—mostly celebrated critics and/or curators trained in nineteenth-century photography, and often the very people who collect, exhibit, or publish his work—in their over-the-top assessments and praises of Struth as the new genius and the direct-line descendant of either Atget or Anselm Kiefer.

That said, Struth’s colossal chromogenic prints must of course be admired for their impeccable technique and painstaking care. His printer also should be commended: the colors and details are unimpeachable, and will not let Struth’s many collectors down.

Before my visit, I had opened the expensive companion book to the exhibition with excited anticipation; I was hoping that I, too, might forgo all jaded sophistication, might fall in love with the world as translated into a Struth postcard, and stand transfixed—like Botho Strauss’s narrator in Saint Mark’s Square. But the alchemy simply does not work. It occurred to me that 150 years ago, the alarmed viewers of Daguerre’s first daguerreotypes—small, shiny portraits on mirror-like metal, no larger than a palm— thought that the faces were staring back at them, so alive were the portraits, so exact the resemblance. Thomas Struth’s photographs fail to move me in that way, in part because of his ambitiousness and the very format he has been so praised for. They do not make it from the page to the wall, and do not stare back at me: big is not beautiful.©

Carole Naggar

"Thomas Struth: 1977-2002” was shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, February 4-May 18, 2003; it will be presented at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, June 28-September 28, 2003.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

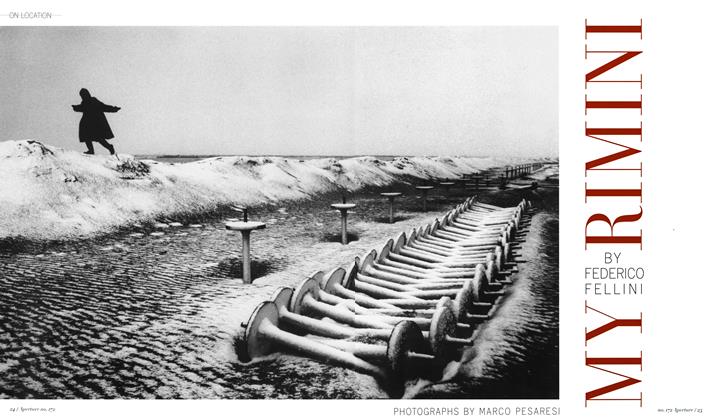

On Location

On LocationMy Rimini

Fall 2003 By Federico Fellini -

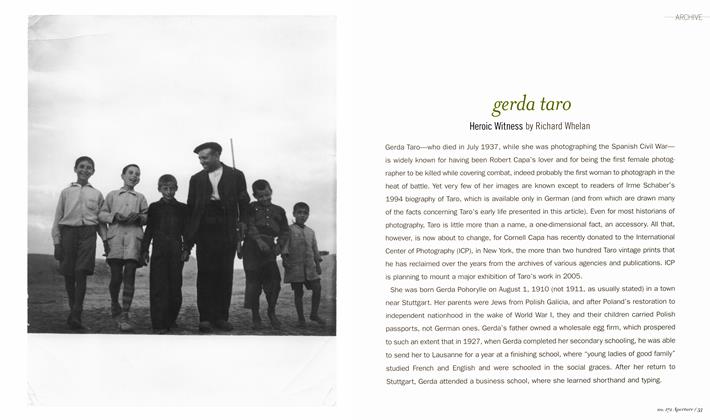

Archive

ArchiveGerda Taro

Fall 2003 By Richard Whelan -

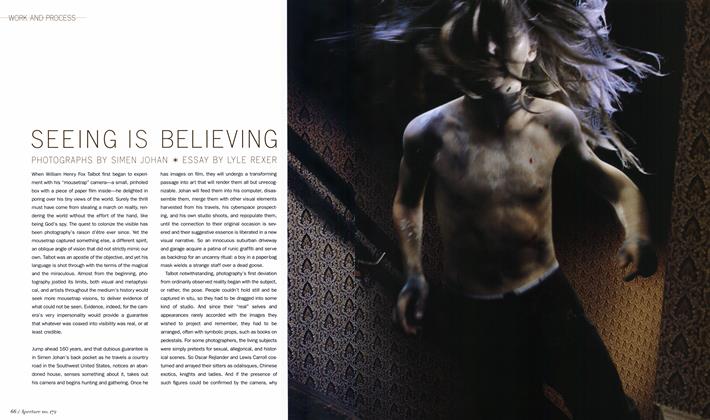

Work And Process

Work And ProcessSeeing Is Believing

Fall 2003 By Lyle Rexer -

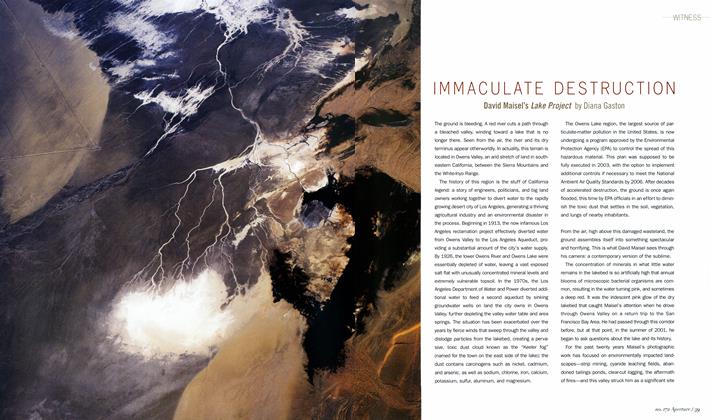

Witness

WitnessImmaculate Destruction

Fall 2003 By Diana Gaston -

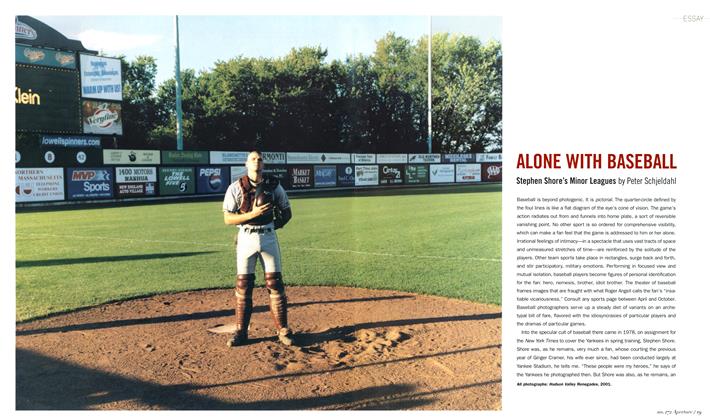

Essay

EssayAlone With Baseball

Fall 2003 By Peter Schjeldahl -

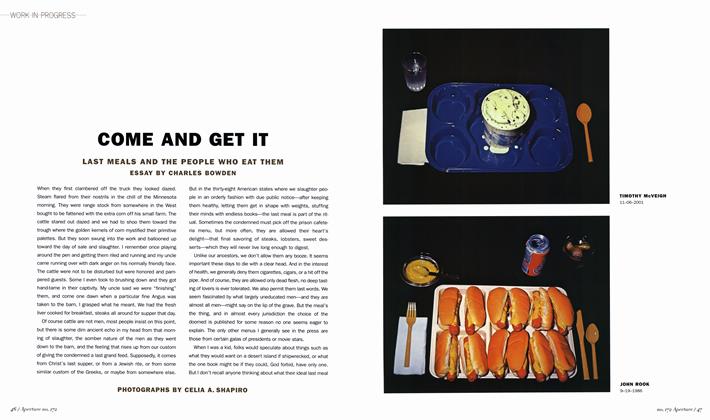

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressCome And Get It

Fall 2003 By Charles Bowden

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Carole Naggar

-

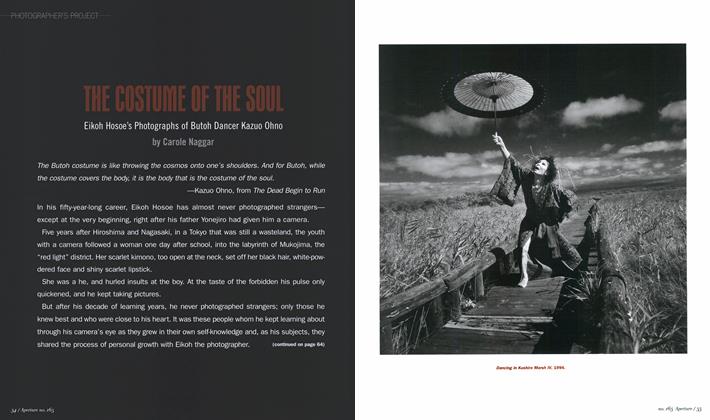

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectThe Costume Of The Soul

Winter 2001 By Carole Naggar -

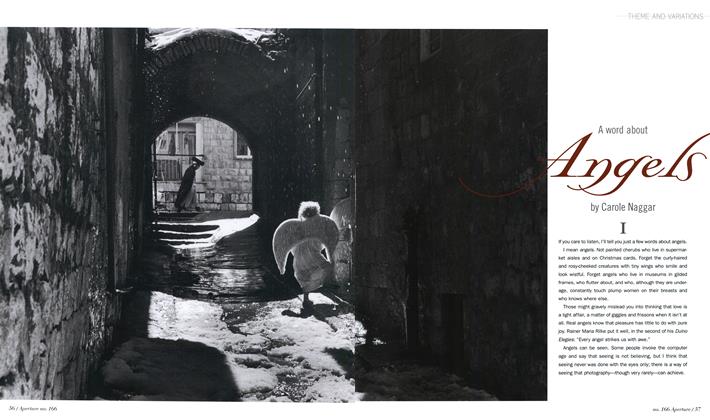

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsA Word About Angels

Spring 2002 By Carole Naggar -

Reviews

ReviewsI Need A Camera: The Films Of Raymond Depardon

Spring 2005 By Carole Naggar -

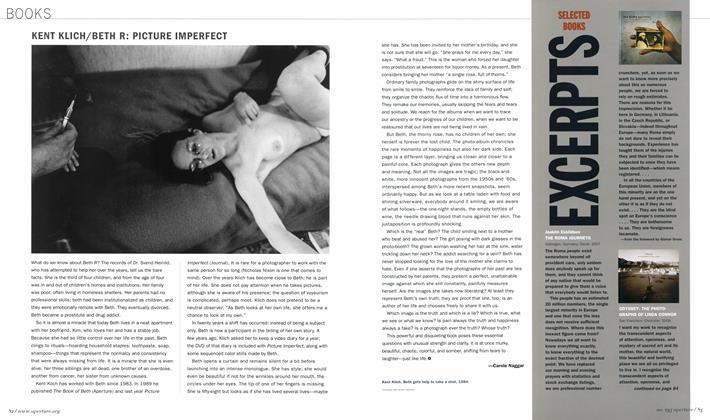

Books

BooksKent Klich/beth R: Picture Imperfect

Winter 2008 By Carole Naggar -

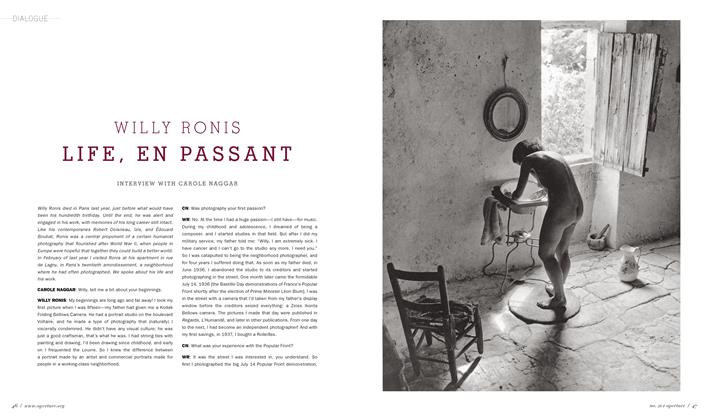

Dialogue

DialogueWilly Ronis Life, En Passant

Winter 2010 By Carole Naggar -

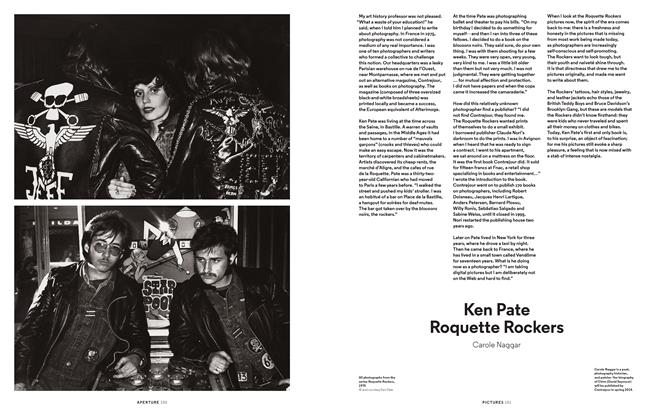

Pictures

PicturesKen Pate Roquette Rockers

Winter 2013 By Carole Naggar

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsThe Encounter Of Man And Nature: The Spiritual Crisis Of Modern Man

Summer 1970 By Haven O’More -

Reviews

ReviewsWolfgang Tillmans

Winter 2006 By James Yood -

Reviews

ReviewsRay K. Metzker

Summer 2008 By Martin Jaeggi -

Reviews

ReviewsThe Modern West: American Landscapes 1890-1950

Fall 2007 By Michael Duncan -

Reviews

ReviewsArt And Photography

Summer 1970 By Robert A. Sobieszek -

Reviews

ReviewsTom Hunter: Living In Hell And Other Stories

Summer 2006 By Susan Bright