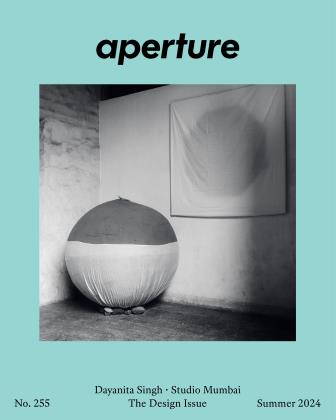

The Theater of Paul Kooiker

Vince Aletti

For all their polish, there’s something about Paul Kooiker’s pictures that feels outsider, something obsessive and off. Even when he’s photographing ordinary subjects—an egg, a wig, a shoe, an eyeball— in a relatively straightforward style, the results look alien. Maybe that’s why the Dutch photographer, who has published nineteen books since 1999, remains a cult figure.

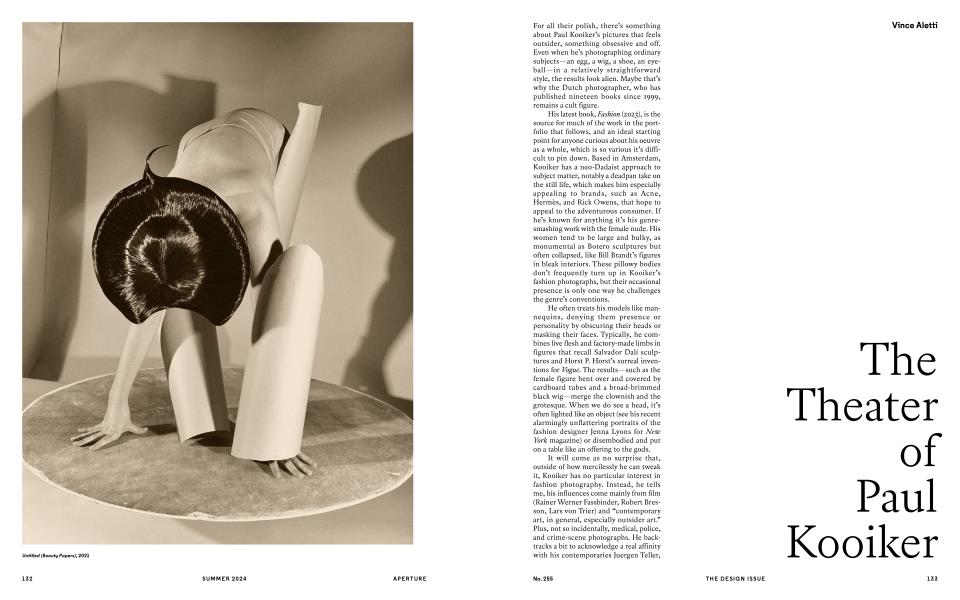

His latest book, Fashion (2023), is the source for much of the work in the portfolio that follows, and an ideal starting point for anyone curious about his oeuvre as a whole, which is so various it’s difficult to pin down. Based in Amsterdam, Kooiker has a neo-Dadaist approach to subject matter, notably a deadpan take on the still life, which makes him especially appealing to brands, such as Acne, Hermes, and Rick Owens, that hope to appeal to the adventurous consumer. If he’s known for anything it’s his genresmashing work with the female nude. His women tend to be large and bulky, as monumental as Botero sculptures but often collapsed, like Bill Brandt’s figures in bleak interiors. These pillowy bodies don’t frequently turn up in Kooiker’s fashion photographs, but their occasional presence is only one way he challenges the genre’s conventions.

He often treats his models like mannequins, denying them presence or personality by obscuring their heads or masking their faces. Typically, he combines live flesh and factory-made limbs in figures that recall Salvador Dali sculptures and Horst P. Horst’s surreal inventions for Vogue. The results—such as the female figure bent over and covered by cardboard tubes and a broad-brimmed black wig—merge the clownish and the grotesque. When we do see a head, it’s often lighted like an object (see his recent alarmingly unflattering portraits of the fashion designer Jenna Lyons for New York magazine) or disembodied and put on a table like an offering to the gods.

It will come as no surprise that, outside of how mercilessly he can tweak it, Kooiker has no particular interest in fashion photography. Instead, he tells me, his influences come mainly from film (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Robert Bresson, Lars von Trier) and “contemporary art, in general, especially outsider art.” Plus, not so incidentally, medical, police, and crime-scene photographs. He backtracks a bit to acknowledge a real affinity with his contemporaries Juergen Teller, Roe Ethridge, and Viviane Sassen because, like him, they “stand with one leg in the art world and with the other in the fashion world.” Kooiker adds, “The pleasure of making fashion pictures is, for me, the dynamic of it. You have to do it most of the time in one day, and it’s never all perfect, so you have to improvise. So even when things go wrong, you have to solve it very quickly. I really like these moments of making decisions very fast without too much doubt. I also love to work on the set design, to create my own world in a small studio with cardboard, smoke, and dust.”

That sense of improvisation animates all of Kooiker’s output, but it’s especially evident in his fashion pictures, some of which suggest a Theatre of the Ridiculous production compressed to a single scene. Others tease the idea of the “important accessory”: showing an expensive leather glove on a hand grasping a slab of soft dough, strewing a fortune in jewels over what looks like a damp bath towel, or sticking five sky-high heels on an array of mannequin legs fanned out from a plaster base (Pierre Molinier’s devil doll, an alter ego of the French artist, would scream with envy). The agility and wit of Kooiker’s improvisations are helped, surely, by the fact that he photographs not with a camera but with a cell phone.

“All my work since 2010 has been made with iPhones,” he said. “Also, all my fashion work. I started out with the iPhone 3 and from then almost every year the latest version.” He’s using the model 15 now and is clearly hooked. “It’s not a big issue for me,” Kooiker added. “I just love the flexibility and limitations of this camera phone, and, in the end, people don’t see it. Most people think my work is made with analog cameras.”

Kooiker is happy to remain at the outer edge of the fashion-image-making establishment, such as it is. If that means his pictures appear mostly in European, avant-garde, alternative style and culture magazines—Acne Paper, Luncheon, Nume'ro, Dust, Dazed, and AnOther—that also means there’s a lot less compromise and editorial interference involved. Asked about photographers he related to, he named two outsider, and for some photoworld insiders, cult, figures: Hans Bellmer, the great German French Surrealist, and Gerard Fieret, the Dutch artist best known for rubber-stamping his name and address all over his slapdash erotic images. “It was a shock when I saw their work for the first time,” Kooiker recalled. “I felt that I was not alone in the art world.”

Vince Aletti is a photography critic, writer, and curator living in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

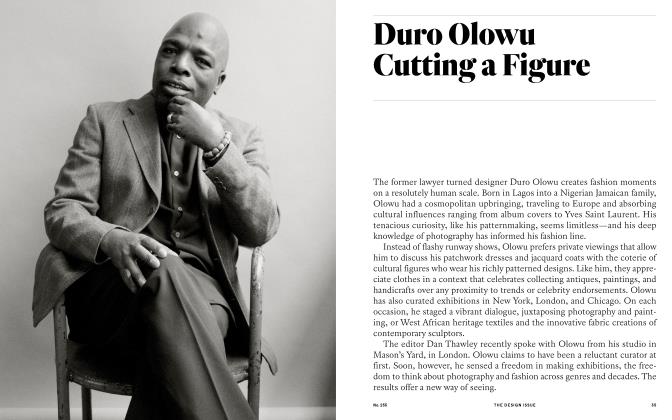

Duro Olowu Cutting A Figure

SUMMER 2024 -

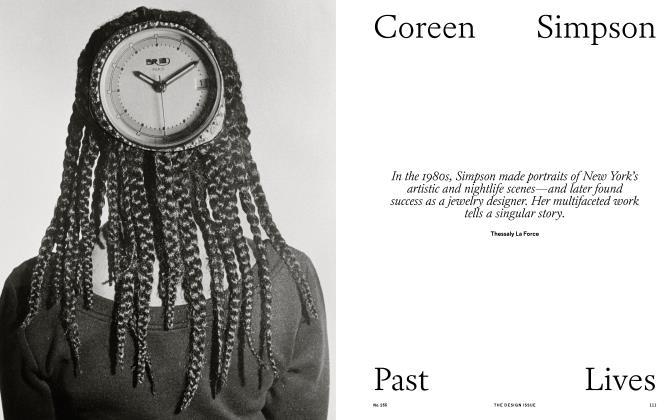

Coreen Simpson Past Lives

SUMMER 2024 By Thessaly La Force -

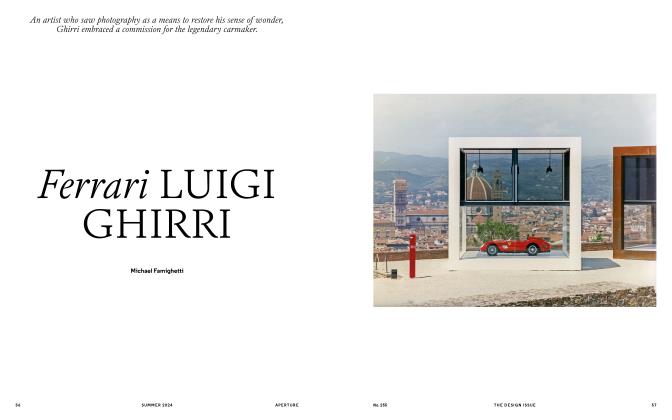

Ferrari Luigi Ghirri

SUMMER 2024 By Michael Famighetti -

David Hartt Paradise Lost

SUMMER 2024 By Mimi Zeiger -

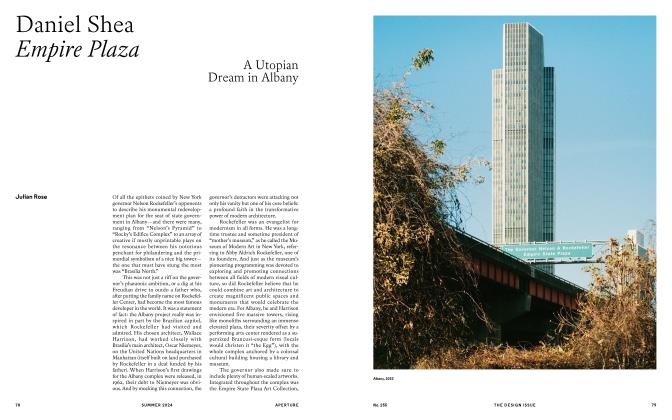

Daniel Shea Empire Plaza

SUMMER 2024 By Julian Rose -

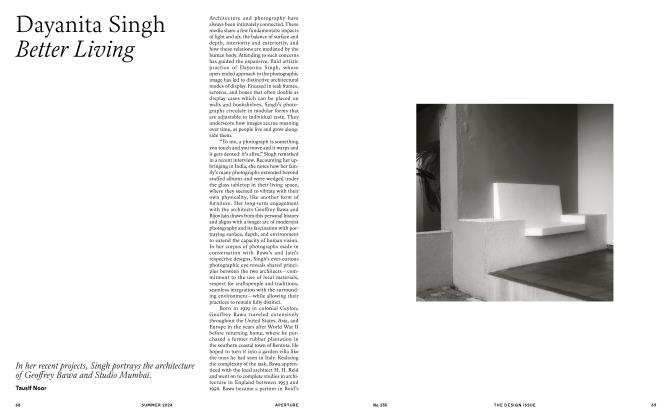

Dayanita Singh Better Living

SUMMER 2024 By Tausif Noor