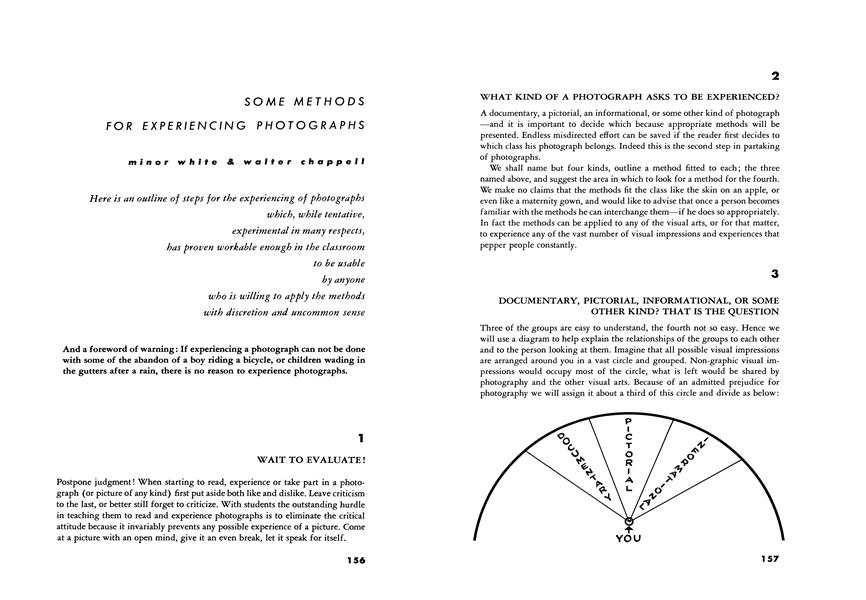

SOME METHODS FOR EXPERIENCING PHOTOGRAPHS

minor white

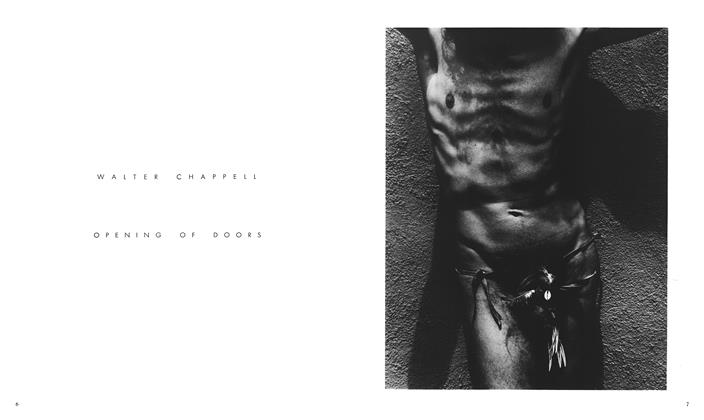

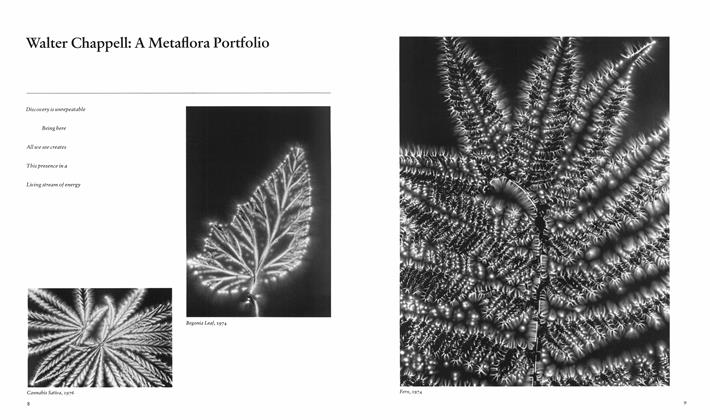

walter chappell

Here is an outline of steps for the experiencing of photographs which, while tentative, experimental in many respects, has proven workable enough in the classroom to be usable by anyone who is willing to apply the methods with discretion and uncommon sense

And a foreword of warning: If experiencing a photograph can not be done with some of the abandon of a boy riding a bicycle, or children wading in the gutters after a rain, there is no reason to experience photographs.

1 WAIT TO EVALUATE!

Postpone judgment! When starting to read, experience or take part in a photograph (or picture of any kind) first put aside both like and dislike. Leave criticism to the last, or better still forget to criticize. With students the outstanding hurdle in teaching them to read and experience photographs is to eliminate the critical attitude because it invariably prevents any possible experience of a picture. Come at a picture with an open mind, give it an even break, let it speak for itself.

2 WHAT KIND OF A PHOTOGRAPH ASKS TO BE EXPERIENCED?

A documentary, a pictorial, an informational, or some other kind of photograph —and it is important to decide which because appropriate methods will be presented. Endless misdirected effort can be saved if the reader first decides to which class his photograph belongs. Indeed this is the second step in partaking of photographs.

We shall name but four kinds, outline a method fitted to each; the three named above, and suggest the area in which to look for a method for the fourth. We make no claims that the methods fit the class like the skin on an apple, or even like a maternity gown, and would like to advise that once a person becomes familiar with the methods he can interchange them—if he does so appropriately. In fact the methods can be applied to any of the visual arts, or for that matter, to experience any of the vast number of visual impressions and experiences that pepper people constantly.

3 DOCUMENTARY, PICTORIAL, INFORMATIONAL, OR SOME OTHER KIND? THAT IS THE QUESTION

Three of the groups are easy to understand, the fourth not so easy. Hence we will use a diagram to help explain the relationships of the groups to each other and to the person looking at them. Imagine that all possible visual impressions are arranged around you in a vast circle and grouped. Non-graphic visual impressions would occupy most of the circle, what is left would be shared by photography and the other visual arts. Because of an admitted prejudice for photography we will assign it about a third of this circle and divide as below:

No normal educated adult will find difficulty with any of the pictures in these groups, even though study will reveal more than he usually realizes is present. But these three groups do not account for all the kinds of pictures that happen in photography. Every now and then something special happens such as Roman Frietag points out in his "Subconscious of the Camera” (aperture, 5:1, p. 5) . As he says such photographs seem accidental, unexpected, "shots at random—and nobody expected them to be anything else—there may be one among them in which the veil is lifted from the surface of familiar objects and some mysterious motivating force is laid bare.” For instance the photographs of spiral nebulae made for strictly informational purposes, which somehow transcends the informational, they have often published for their aesthetic value. Such unexpected photographs appear in the other classes too, occasionally a documentary photograph transcends its subject, or a pictorial photograph transcends both its subject and its manner.

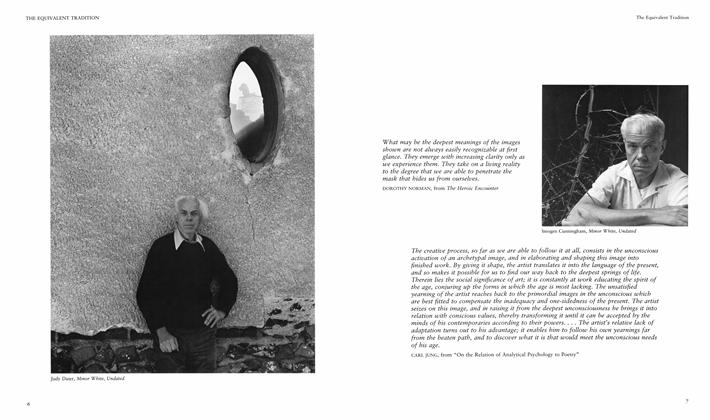

For all their being extraordinary, infrequent, difficult to either account for or understand "Equivalents,” as such pictures will be named, constitute the fourth group.

The name "Equivalent” is given to this group in honor of Alfred Stieglitz, who was one of the first to try to turn the happenstance photograph which transcended both subject and manner into his consistent and customary manner of working. In his later years when success attended his efforts he called such pictures Equivalents. His cloud sequences are the best known examples. He attached great meaning to this word ; he came to call any work of art, regardless of medium, painting, photography, living, equivalent.

It can be surmised from the diagram above that "Equivalents” constitute a homogeneous group. Even though Equivalents happen to photographers who habitually work in one or more of the other three classes, they are still more alike than different on essential points. Note also that the area in the diagram allocated to the Equivalent does not have a closing side: this is to be understood as saying that this field is still wide open for exploration.

4 BECAUSE ALL PHOTOGRAPHS ARE HERE TOSSED INTO FOUR PILES

and four only, the reader who proposes to decide into which class a specific photograph belongs needs some definitions.

DOCUMENTARY

Photographers who pursue documentary photography have a deep seated belief that the photograph takes the spectator somewhere. The photograph transports him from where he sits to other lands, or bridges time—usually backward. Hence to him the photograph is a vehicle or bridge. Consequently when one deals with the documentary photograph, one never reads the photograph for its own sake, one reads a character, or an event, or a place. The photograph is a splendid device, even the most superior device ever invented for holding a transitory instant still long enough to look at it in leisure—a kind of instantaneous deep freeze. If it’s a single head, one reads the lines of character; if an event, one reads the clues of costume, gesture, geography, ashcans or palaces.

In the sense of "pure reporting” or "direct transference” Ansel Adams reporting the natural scene is as documentary as Lewis Hine who reported the social scene.

Photographers in this class often adhere (tenaciously) to the dogma "content above all.” Edward Steichen says of this attitude, ". . . the superfluous things he can’t keep out. Maybe the answer is that he shouldn’t try to keep them out. Maybe that is photography.” Consequently when the superfluous appears one must forego reading any relation between background and subject because it is involuntary. (Some of the involuntary statements that get made this way are hilarious or naughty or embarrassing.)

An example of the incidental background appears in the Dorothea Lange photo on page 146 of this issue. In contrast, Ansel Adams’ picture "Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” contains nothing irrelevant. It can be read for everything that can be seen.

The souvenir photographs also belong in this group.

The photoreporter as well. Perhaps a quote from LIFE in 1936 would help define the attitude of "documentary” as used in this outline:

To see life, to see the world, to eye-witness great events, to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud, to see strange things, machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon ; to see man’s work, his paintings, towers and discoveries ; to see things dangerous to come to ; the women that men love and many children; to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed ; to see and be instructed ; thus to see, and be shown, is now the will and new expectancy of half mankind.

Dorothea Lange’s "Three Women Walking” is an example, page 146.

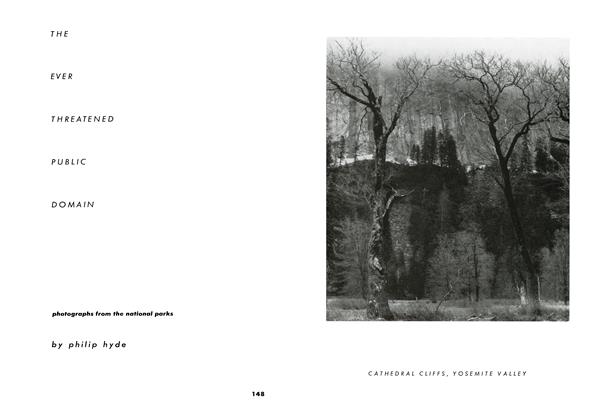

PICTORIAL

A pictorialist never forgets that he is making a photograph ! He deliberately makes manner underline statement and the graphics of the medium augment content. Consequently every last visible speck contributes something to the totality and may freely be read.

A fine definition appears in the 1957 FOCAL ENCYCLOPEDIA. A. Krasza-Krauz wrote it and how broad it is. Essentially he says that the pictorialist is "less concerned with the subject than the picture it will yield.” He uses the camera not so much "to record as to stress how he sees.” And whether the various schools like it or not, the definition includes the salon pictorialists, the pure photographers, the subjectivists, the modernists, and the future schools and individuals who seek to make manner as important as subject matter.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, who is not regularly associated with pictorialism, by his own statement says in THE DECISIVE MOMENT: "For me content can not be separated from form. By form, I mean a rigorous organization of the interplay of surfaces, lines, and values. It is in this organization alone that our conviction and emotions become concrete and communicable.” And then goes on to say "In photography, visual organization can stem only from a developed instinct !”

The photographs by Philip Hyde in this issue belong to this group, as do those by Tom Murphy and Jerome Liebling.

INFORMATIONAL

Pictures which explain, instruct, report, acquaint the mind. Science, industry, the mundane world put photography to a thousand thousand uses whose main purpose is to inform the mind.

Science uses photography to help remember, to count, to see stars and microbes which man with his unaided senses can not. And it is mainly from this research employment of the medium from which photographs emerge that not only inform but frighten, by the proximity of unknown worlds.

Applied photography applies to a multitude of occupations. Aerial mapping to Zoology; copy photography to microcopy of pages to macrocopy of works of art. Most architectural photography is a form of copy with those rare exceptions when the facts reported somehow stir the emotions.

Reading such photographs depends a great deal on specialist knowledge. To the layman, scientific photographs, for instance, affect him as equations written on a blackboard affect a mathematical idiot. There is an example on page 170.

EQUIVALENT

According to Alfred Stieglitz an Equivalent was a photograph that "stood for” a feeling he had about something other than the subject of the photograph. (Thus far he is a pictorialist.) He often said that he could deliberately make a photograph that would be the equivalent of how he felt about some friend. And then scan the skies until some passing cloud formation would, when photographed, be such an equivalent. It must be noted that "how he felt” here referred to his notion of the inner nature of the person. When he looked for a photograph no attempt was made to imitate the outer features. These features which are visible to the physical eye Stieglitz thought revealed the inner face like a clear glass window pane transmits but does not change the shape of the landscape.

The Equivalent can be defined in still another, almost mechanical way. Any photograph is an Equivalent, regardless of whether a pictorialist, scientist or reporter made it, that somehow transcends its original and customary purposes, i.e., transcends instinctive subject, emotional manner, and intellectual information, and furthermore transcends these parts in unison.

A very important part of the definition of an Equivalent still remains. Such a picture must evoke an emotion, and a very special emotion at that. It is a heightened emotion such as the East Indian would say "takes one heavenward” or Bernard Berenson would say is "life-enhancing.”

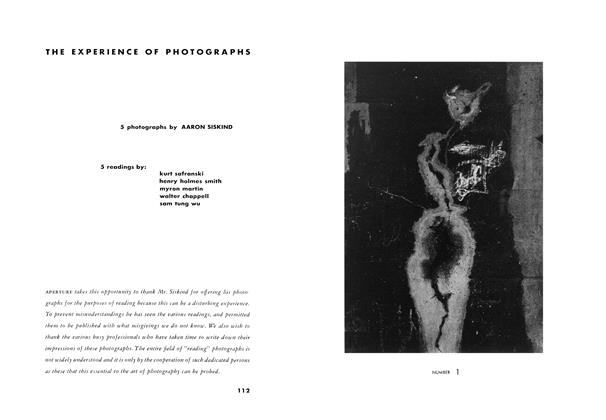

An example by Stieglitz appears in aperture, 5:2 on page 72. Another is Aaron Siskind’s "Pertining to Flight,” page 143.

5 FOR EACH OF THE CLASSES AN APPROPRIATE METHOD

of reading is outlined. But first a brief pause to point up a pair of convenient pitfalls. One has to do with the terms "experiencing” and "reading.” We could use them interchangeably, but we will not. The first will stand for an end, the other for a makeshift. Experiencing a photograph or living with it, or growing with it, or journeying through it, is a private, personal business. It is a private conversation carried on between a man and a photograph, and it is significant only when it is carried on by a man and a photograph. Reading a photograph must follow experiencing it. Reading a worthwhile photograph in public at first sight even by an expert is a superficial performance, done under stress and justified only in the interest of education: done only to encourage with know-how people who are capable of experiencing a worthwhile photograph.

The other pitfall has to do with a distinction between "photograph” and "image.” The former will be considered as the physical object, two-dimensional with a surface and just beneath that surface shades of gray or color disposed variously. Image is the mental completion of the photograph.

The image in our minds is the rounding out of the illusion of depth, the identification of the grays as something seen elsewhere.

Furthermore "image” implies valuation: photographs that fail to impress we dismiss lightly. Only those that interest us or that we like well enough to take into our minds do we call "images.”

This distinction is made to help prevent confusing the photograph with the original which everyone is prone to do. And to bring home the fact that one really experiences or reads, not a photograph but an image. This is a distinction that customary speech does not make clear. It only seems accurate to say that we read the photograph, but actually we read images in our mind. And the word "image” will be used throughout in exactly this meaning.

One pitfall that is especially pleasant to drop into for a rest now and then is the notion that the steps as given in this outline are rigid. Anything but . . . steps simply have to be put in some order. The variety of photographs is so great that no order could be found that really fits them all. So what seems to be the order here is mainly a check list. The experiencing of a photograph is a personal thing and therefore its course is unprescribable. That feature of a photograph which acts as a magnet for you is the starting point. Hence start with the magnet and follow its lines of force as you feel them to the end of the journey of a photograph. This is for the spectator first, and for photographer as he plays the role of spectator of his own pictures. Role is not the right word ; spectating his own photographs is part of the rhythm of making his pictures—taking the pictures is the down beat, reading is the up beat.

METHOD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHS

1. Note whether background is intended to relate to subject or is unintentionally superfluous. If the latter, please disregard ; if the former, anticipate relating.

2. First impression of as much of picture as seems intentional. Tag impressions with a word or a phrase so as to be able to remember it at any moment during the experience of place, face or event.

For example, Dorothea Lange’s "Three Women’’:

Your prst impression might be tagged "three ages.” If you are a beginner, whatever this means to you is enough—you don’t have to tell anybody. An expert with a patiently developed reading instinct alone need worry about correspondence between prst impression, last impression and what photographer thinks he means by the photograph.

3. Now follows a long or short period of observing everything visible and pertinent, and letting nothing pass that might be a clue. Key to what ? Symptom of anything.

There could be some value in creating a hierarchy of clues to follow in some loose order, but with a two-dimensional surface there is so little possibility of the photographer’s controlling the order of observation, and such a great variety of pictures that we will spare ourselves the trouble. We do advise gallantry in observing and suggest that the reader demand no clues not present.

A. If the photograph is primarily of one person:

Search for clues that will reveal what sex, what nationality, what race, what occupation, what type, married or not, what mental state, how much of photograph appears, what person would do in a rainstorm, in an automobile accident, is he crippled in any part of his body or mind, or ill there—the list is next to endless. Since your first impression was probably one of like or dislike, someone to go to bed with or avoid with all skill, you may find that you have changed your mind about the person. In any case you "know” more about him.

B. If the photograph shows two or more people:

Employ all the hints whereby each person can be experienced. In addition seek the keys to the relationships between all people recorded: gesture, costume pressed or wrinkled, position and that piece of paper one has just signed and the other received.

C. If the photograph is a document of an event:

Search for all testimony which will reveal where, what, condition of place, action of participants, and especially for the aura or atmosphere whereby the nature of the event can be ascertained: belligerent, exuberant, growing, carnival, or whether death struck in the midst of merriment, or a wedding procession intersects a funeral march.

D. If the photograph is of a place:

Find the clues which will tell you who just left, how long gone and when they will return. Look for the annotations of social strata, hovel, juke box or palace, and especially for indications of the atmosphere of house or home. Or a street the people love or meet their maker in, or find torment unto Hell. If a scene in nature, what kind of person would give up a good job to live in it? Or where can you trace a divine finger print?

In any of the general situations listed above keep on the constant lookout for symptoms of relationships, present or absent and the nature of. Invariably one relationship is always present, the one between yourself and the photograph. And if you have scrutinized, observed, and otherwise run down every spoor, you will discover that some kind of bond has been established. This bond will vary directly as you yourself are, and indirectly as the wind blows. Consequently no check list can predict such bonds : small loss, because for the duration of the bond you have lived.

Here is another handy pitfall. While experiencing photographs we forget that when we put the photograph down the experience leaves traces in us. If you experience what a documentary photograph holds still long enough for you to study, you will look up with a new insight on the world. If it shows you what you had not seen before, for a few days thereafter many examples ivill hit you from the host of visual impressions impinging constantly. While it lasts such recognition enhances living.

4. Compare first impression with concluding one: you may discover that the train let you off at a distant station ; or simply that what was a first impression is now a conviction—round trip.

5. With the experience or the journey behind you, now find the words to tell the story of your trip, and describe as effectively as possible the terminal where you debarked.

METHOD FOR PICTORIAL PHOTOGRAPHS

1. First impression: since all of a pictorial photograph is readable one starts with tagging the first impression.

Except that one can respond without reservation, this step is little different than its counterpoint in the method for Documentary photographs.

2. Observe the geography of the photograph. First with the view of noting its details and second to discover how the geography augments the content or underlines the first impression.

This work is admittedly intellectual and analytical, hard work and objective. The geography falls conveniently into three sections : graphics, concepts and design. All three of which must be considered with their appropriate emotional connotations.

A. Graphics appear in photographs as the result of controls inherent in the medium. We shall name five ; there are more, none of them hard to discover.

Continuous Tone when combined with lens sharpness and emulsion resolution can achieve lucidity and clarity of image that is unique to photographs, or it can be controlled to yield posterlike discontinuous tone. The first connotes a love of the medium which enhances objects, and the second a confusion between painting and photography.

Control of Motion can either freeze things moving so fast (bullets in flight) they can not be seen by the eye; or with slow shutter speeds achieve blurs such as the eye never sees either.

In between is also characteristic of photography.

The derivations from unique photography are many and those that cluster around solarization will serve as an illustration. To most photographers this is a no-man’s land between painting and photography and few have been able to perform with real joy in this area of continuity between the two media.

The Negative Image is the most commonplace talisman of magic in the whole visual repertoire.

Multiple exposures and Multiple negatives, control of perspective and over all tonal control are other graphics to be watched for.

The above is incomplete simply because space forbids. But since

emotional connotations which can be associated with the various graphics are partly a personal affair, discovery of them for oneself is all to the good.

B. Concepts are groups of visibles in pictures which border on the intangible.

Light. What kind is present? The illusion of a high overcast which reveals objects at the expense of itself? Directional light such as sunlight which casts and carries a sense of euphoria? Light from lamps indoors so very different from sunlight? Or a flash which lights things with all the grace of a punch in the nose? Or light that seems to come from within the object itself, which always evokes a not quite reality.

Space. The sense of three-dimensional space found in photographs is one of its most fabulous illusions. Limited space may suggest a sense of intimacy or confinement, or sometimes a mixture of both. Distant space evokes a nostalgia for anywhere out of this world: is this what the photographer wants to convey? In some photographs the sense of air all around its depicted objects magnifies the blatancy, in others heightens the very mystery of existence.

A thousand subtle variations exist, the search for which is part of experiencing a photograph.

Form. Form in its largest sense is not intended here, merely a polarity of closed form and open form with all the intergrades between. At one extreme is open form which can be identified by the incompleteness of all or most of the objects seen; heads cut in half, windows chopped, parts of cars, etc. The effect is to give the photograph the feeling of having been cut out of whole cloth, or lifted so recently from life that the fish is still wriggling. At the other extreme closed form exhibits all its inner forms complete ; whole heads, or whole bodies, all of a car, an entire window, wall, house. It evokes the sensation of completeness within the picture, and the sense of isolation that is a microcosm of the world at large, or a private world into which you may enter if you wish.

Other concepts are possible ; one can group various manifestations in a variety of ways, for instance tactile textures arouse sensations that the hand can feel, visual textures those subtile tex-

tures such as sparkle on water eyes can enjoy but no hand may feel. Or classify the edges of things from smooth and sensuous to jagged and repellent.

In observing such features of the geography of a photograph one can be relatively certain that very, very few photographers have ever done the same with their own pictures. But this is a matter which ive hope will change in the future.

C. Design. Observe the organization of the features of the geography, what general movements animate the total visible effects. If the design is formal or symmetrical it indicates the movement of standing still ; if informal the movement of action. If symmetrical it also indicates that an intellectual logic is at work ; if asymmetrical, made to balance by the most subtle of tensions playing against directions, an emotional logic such as the Romantics favor is present.

When the observation and analysis of the geography is done, considerable experiencing of the photograph has taken place, and the pitfall to be avoided here is the temptation to climb the hill of some features of the geography and wing off on a delightful flight of fancy. What is learned from observation has a later use; the knowledge gained will help the verbalizing stage of reading.

3. Experiencing the subject in those pictorial photographs which exhibit recognizable subjects. Do so in the manner suggested for Documentary Photographs.

The beginner is most likely to experience the subject before he attempts to observe the geography. Only the disciplined reader can guide his steps. Fortunately strict adherence to the order of the outline is nonsense.

4. Explore the whole fanciful world of "what does this remind you of.” This is subjective and subject to all the mild dangers of flights of fancy and trips to a wild blue yonder on no more than a single feather—unfortunately. Board the train of associations —unknown destinations can become familiar in no other way.

In those pictorial photographs ivhere the camera has moved in so close to a familiar subject, such as the side of a barn, that it becomes unfamiliar there is little other way than associations to experience the photograph. For example the Siskind photographs in aperture 5:3 which incidentally are no more ”ab-

jtractions” than a straight commercial portrait. They just happen to resemble paintings of the abstract or non-objective persuasions.

When a spark from a photograph expands in your own mind like a flood, the experience is so delightful and so noisy that it drowns out any possibility of hearing the still small voice of the photograph itself.

This is the most wonderful pitfall of all: lined with stars, stored with goodies, stuffed with your own golden thoughts, it sways like an ivory tower in a hurricane. Fortunately you don’t have to tell anyone about the irrelevant associations.

5. Sort out the associations:

In tranquility, then, one sorts out the associations. The idea is to isolate those associations which, with only a slight stretch of the imagination, seem to pertain to the photograph. In this way what was at first a rosy infatuation may grow into a sincere emotion.

6. Verbalize.

The essential problem here is no different than the corresponding step in the method for Documentaries. The difference lies in that the tale of the jaunt can be told as if the journey took place across the geography of the photograph ! The graphics, the concepts, the design and all the other visuals are the very means to tell another person the tale of the pertinent associations. With the visuals which you can point your finger at you can show how the manner fits the statement.

METHOD FOR INFORMATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHS

1. Acquire a working knowledge of the special field from which the photograph originates; e.g., astronomy, bacteriology, to name two of thousands. Then proceed as in Documentary photographs to read the subject and not the photographs. Informational photographers always treat the photograph as a means to an end. Doesn’t one "read” the pages of the books that have been microcopied?

Acquisition of the necessary knowledge may be difficult or rel-

atively easy. While everyone knows the traces of man on the landscape, when one sees an aerial photograph the roof of one’s own house may be unrecognizable. "Photointerpretation” however, because of general knowledge, is not difficult to learn. Lacking specialist training, read the caption. Those pictures that result when photography is used as a tool of scientific research rarely reach the general public without some expert’s explanation attached—however garbled.

2. Bypass information and observe for aesthetic qualities. The photographs may be then experienced as a Pictorial and the various steps of that method may be applied as far as they go. Graphics and design will always be pertinent, the concepts sometimes; "what does this remind you of’’ is rarely closed to exploration.

Photography has been used in science for many decades and consequently a considerable body of photography exists, and which are ividely seen, ivhich materialize what the unaided human eye can not see—the bullet in flight.

As Gyorgy Kepes says in his THE NEW LANDSCAPE IN ART AND SCIENCE a veritable world of knoivledge is with us and which science has pictures of, but which, as yet, the lay public can not comprehend intellectually. It is his contention that an aesthetic experience or emotional experience of some of these pictures is possible, and that while it is independent of the informational purpose of the photograph is still a step towards making this kind of information a part of mankind. With this contention Kepes makes experiencing these pictures, on an emotional level, or with the emotional side of man, necessary to mankind’s growth.

3. Verbalize.

Explain or expound the informational content if possible. If the photograph is being treated as a Pictorial there will be no possibility of relating manner to content, so where aesthetic values are verbalized this special situation must be made clear.

Where the informational can function for some persons (nonexperts) as an Equivalent, the acquired purpose is more significant to him than the original.

EXAMPLE OF AN INFORMATIONAL PHOTOGRAPH

An airfield in the Middle East ploughed up before it was abandoned by the Luftwaffe in order to delay or prevent its use by the advancing Allied Air Force. And this is what a photographic interpretation expert has to say, after a detailed examination of this strange photograph:

. . it can be definitely confirmed that the complicated clock movement is in fact the result of the ploughing up of the area. That it should appear so dark is no doubt due to the very red soil. The following points may be of interest:

"The work was presumably done by a tractor towing a plough. Three tractors were employed. They all started from A (right side).

"Tractor 1 went to B and started ploughing from the center outwards. He was a bit 'jerky’ on his driving. (First large circle on right.)

"Tractors 2 and 3 proceeded to C (second large circle from right) where Tractor 2 started ploughing from the center outwards. He ploughed very closely.

"Tractor 3 went on from C to D (third large circle), where he started ploughing from the center outwards. He was somewhat of an artist, and made a very neat job of it.

"Their subsequent movements are of some interest. For instance: Tractor 2 made the little circle at E after finishing C. He then went on and did circle F. Tractor 3, after circle D made circle C. At this point they either packed up for lunch, or for the day. At any rate they subsequently came back, but now having awkward shapes to fill in they started at the outside and worked inwards. Hence the uutidiness of some of the other parts.”

WE WISH WE WERE SURE OF A METHOD FOR EXPERIENCING EQUIVALENTS

To come upon an Equivalent is like finding a bottle washed in on the tides along the stretches of open beach. Inside, who knows ; a message, a cry for help, directions for buried treasure, or even history of a sunken world ?

Tët it is far from easy to recognize an Equivalent among a group of photographs, especially Pictorial ones. Any form cast up on a beach may contain a message. In addition to a method for taking part, one needs a set of criteria for identification. And how wonderful it would be if we could ask the photographers themselves about these Equivalents that they drop during their exceptional moments along the tideline between our everyday landscape and the ocean of our subconscious. Unfortunately they are not much help. There are those who discover that something "happened to them” only after the event, only when they see the finished print. Others, not quite so obtuse, see and suspect during the interim of exposure that something unusual is winking at them. Others more perceptive still occasionally sense that something important is happening to them: a whole afternoon may pass in this state—and the photographs are afterwards evidence to him that it was not all a dream. Such photographers may be thought of as picking up bottles on the beach. Some look at these finds as mere curiosities and don’t even bother to break it open to read what is inside. Others are profoundly moved by the message but fear the implications of self revelation and thereafter shun all such experiences. A few have the curiosity and the courage to deliberately search for these, as Wordsworth called it "intimations of immortality.”

Actually one of the safer identifying marks of the Equivalent is a feeling that for unstatable reasons some picture is decidedly significant to you. Or again, after subjecting a photograph to one or all three of the methods heretofore given, you are tormented by the feeling that there is more.

We are sympathetic to your disappointment after such a buildup to have a method only hinted at, not outlined.

Fortunately an article on reading Equivalents by Mr. Chappell will appear in the Summer issue of the quarterly. Meanwhile if you wish a tentative example of a method refer to aperture 5:3 and Mr. Chappell’s readings of the Siskind photographs.

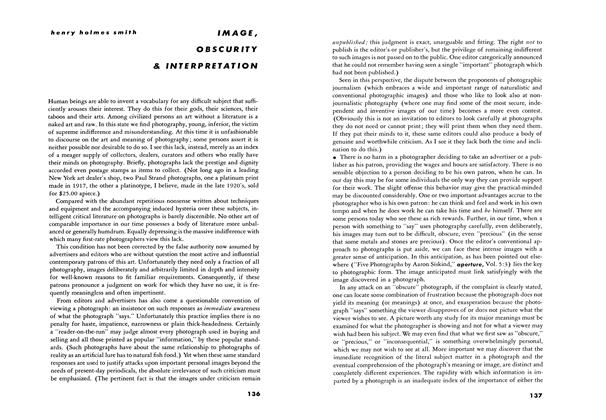

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Minor White

-

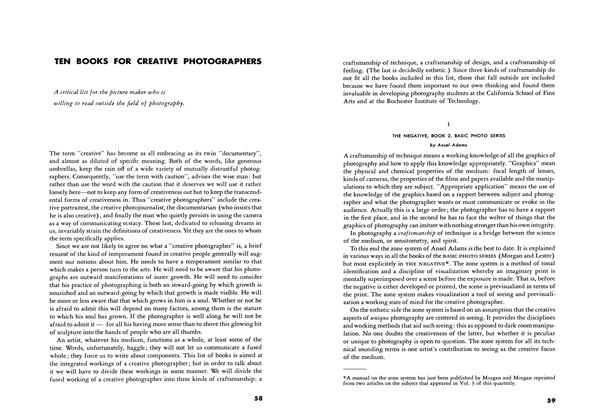

Ten Books For Creative Photographers

Summer 1956 By Ansel Adams, Stephen Pepper, Gygory Kepes, 4 more ... -

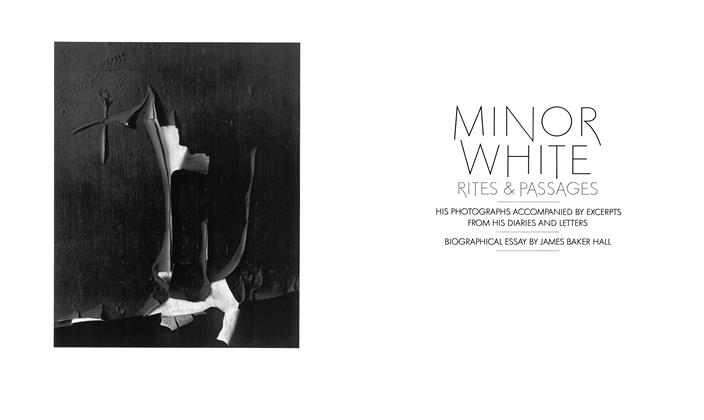

Minor White: Rites & Passages

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall, Michael E. Hoffman -

Editorial

EditorialPhotos For The Athlete

Summer 1957 By Minor White -

Light7

Summer 1968 By Minor White -

Introduction

Spring 1970 By Minor White -

Notes To A Visual Editorial

Fall 1992 By Minor White